Lately I’ve been interested in Southern California Edison, the second largest electric utility by revenue in America. That gives me something in common with a few dozen Altadena residents and their lawyers, who are suing SoCal Edison for starting the Eaton Fire, which killed 17 people and destroyed almost 10,000 structures. Erin Brockovich has gotten involved so you know it’s serious.

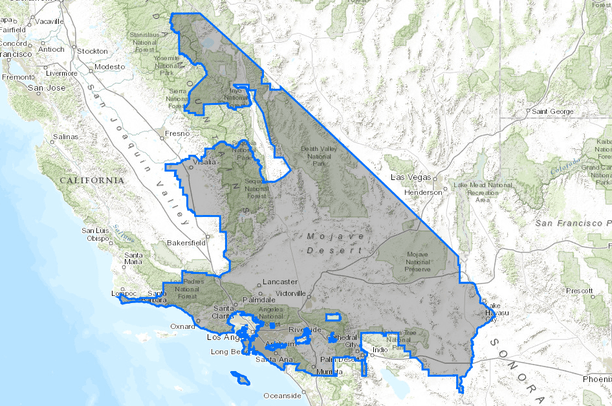

SoCal Edison is an investor-owned utility, which means that it is a private company that provides a public service. Their territory covers 15 million people across 50,000 square miles, including almost all of LA County except the cities of Los Angeles, Glendale, Pasadena, Burbank, Asuza, and Industry, which operate their own public utilities.

SoCal Edison is not affiliated with Consolidated Edison in New York or Commonwealth Edison in Illinois or any of the other Eds. All of them are named after Thomas Edison because he would only let utilities buy his patents if they named the entire company after him. (One of the main reasons the movie industry ended up in Los Angeles was because Thomas Edison was famously revengeful against anybody who used his Kinetograph camera technology without a patent, and Southern California was about as far away from Thomas Edison as you could get.)

Maybe you’re thinking of starting your own power company and are interested in learning how SoCal Edison became the sole electricity provider for one-third of California. More or less it was by absorbing a lot of smaller power companies.

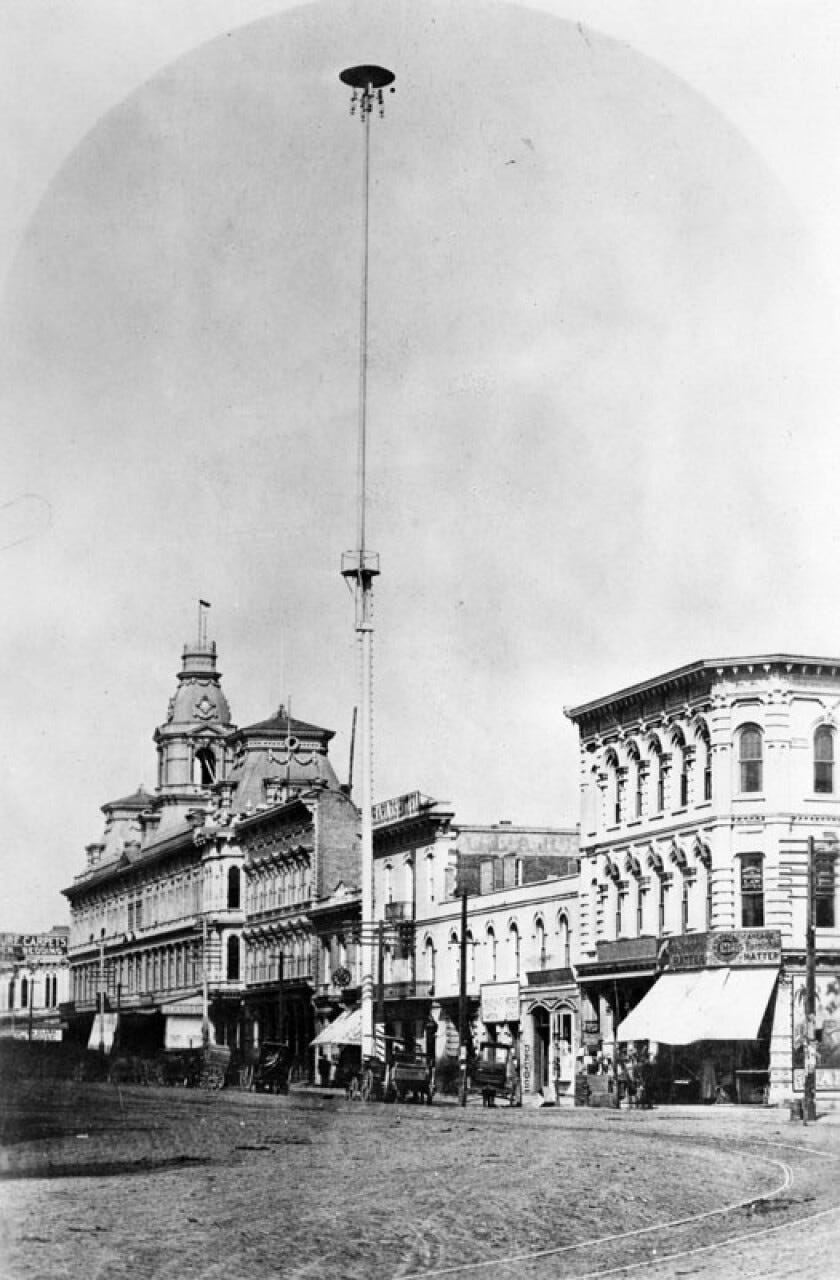

In the late 1800s, mom-and-pop electric utilities were forced in basically every medium-to-large town in the state. Most of them operated carbon arc lamps that were so freakishly bright they had to be raised on masts a hundred feet in the air, essentially acting as a neighborhood sun. The first one in LA was on Main Street in Downtown, right by El Pueblo:

These lamps made very loud exploding sounds at all hours and someone had to go up and replace the carbon rods every day.

At the turn of the century, Westside Power Company in LA started buying up and merging with all the little zap-shops in the region, and the consolidated mega-utility eventually became Southern California Edison. They built their first headquarters on 5th and Grand across from Central Library. The building is still there and has a ground-floor Sweetgreen.

The company headquarters has moved to Rosemead, but their power infrastructure is everywhere — including some large transmission towers in Eaton Canyon above Altadena.

Speculation that those towers had started the Eaton Fire started emerging pretty much right after the fire started the night of January 7th.

Not so fast, SoCal Edison responded on January 9th. We have examined the data and found that X user @WetDirt2000 is wrong and nothing weird happened.

…preliminary analysis by SCE of electrical circuit information for the energized transmission lines going through the area for 12 hours prior to the reported start time of the fire shows no interruptions or electrical or operational anomalies until more than one hour after the reported start time of the fire.

But wait: a guy named Bob Marshall has something to contribute.

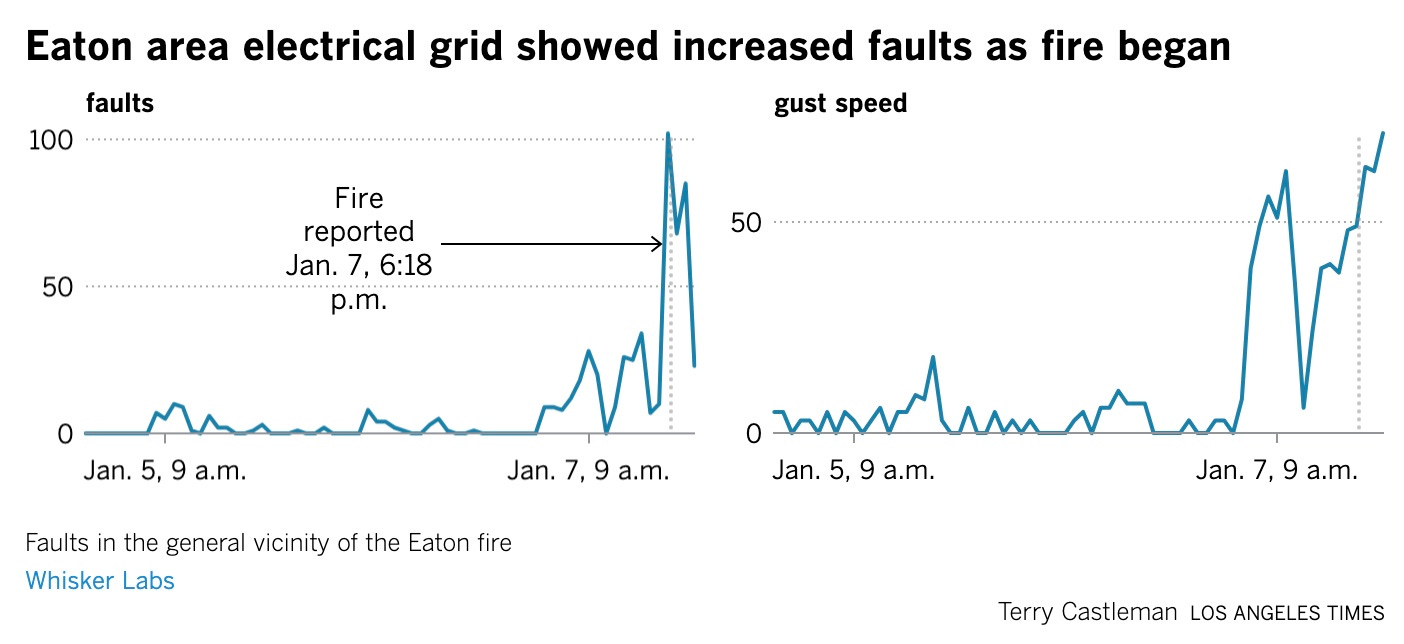

Bob runs Whisker Labs, a company that puts sensors in people’s homes that prevent electrical fires but also provide a picture of overall activity in the area. And the same day SoCal Edison said they hadn’t seen anything unusual on their transmission lines, Bob told the LA Times that the grid near the Eaton Fire was going completely apeshit before the fire — specifically in the minutes before the fire was reported.

Maybe SoCal Edison hadn’t seen that in their preliminary analysis. But their investigation was continuing, and on January 25th they revealed the discovery of a potentially major clue: evidence of a homeless encampment a mere 300 yards downhill from the towers.

In a letter to plaintiff attorneys, reviewed by The Times, Edison said the camp included two fire rings, food and remnants of a tent.

“It appears that the campsite was occupied shortly before the Eaton fire ignited,” the letter, obtained by The Times, reads.

Utility officials also found pieces of metal and debris near the electrical towers over Eaton Canyon, according to the letter.

We all know how much homeless people love pieces of metal and debris. Had they dragged some of it over to the towers and set it on fire during an 100mph windstorm?

Then two days later another video was published in the New York Times. This one, from an Arco gas station security camera, captured photos of two bright flashes in the approximate location of SoCal Edison’s transmission towers in Eaton Canyon a few minutes before the fires broke out, and exactly as voltage readings on one of Bob’s sensors plummeted:

The two electrical disruptions along transmission lines were so powerful that they reverberated as far away as Oregon and Utah, across tens of thousands of sensors.

“We looked at this one — it was like, Holy cow,” said Bob Marshall, co-founder and chief executive of Whisker Labs.

Then another freakin’ article, this one on February 1st from the Washington Post, published evidence that a SoCal Edison tower in the canyon that was decommisioned in 1971 had reenergized and started the fire during the high winds. This article disappointed SoCal Edison.

A spokesperson for SCE said that “it is disappointing that the plaintiffs’ attorneys appear to repeatedly approach media when they should be sharing information with the authorities.”

SoCal Edison still hadn’t reported any evidence other than the homeless encampment — until today! Today, February 6th, they came forward with a report that their technicians had found irregularities on January 19th when testing their equipment.

Why had these irregularities gone unreported for almost three weeks, and only after incriminating evidence was published in the LA Times, New York Times and Washington Post? Why had the company implicated a homeless encampment a week after technicians had already discovered a potential malfunction in their own equipment? Was it possible that the company was aware of potential liability from the beginning and had withheld the data for as long as possible? Possibly to prevent a different kind of jagged line graph incident from taking shape?

This would not be SoCal Edison’s first alleged evidence-withholding rodeo. Just last year, the federal government issued a complaint concluding that SoCal Edison equipment had started the 2017 Creek Fire near Fresno, and it had taken seven years for investigators to figure that out because the company had deliberately suppressed evidence and tried to pin the fire on LADWP.

“SCE breached its duty of care and was negligent in causing the Creek Fire, including its failure to construct, maintain, and operate its power lines and equipment in a safe and effective working order,” the federal complaint said.

SoCal Edison, for their part, said that the whole thing happened because somebody at the company turned over the data ~*~from the wrong day~*~.

The attorney for Edison claimed the entire situation arose from an inadvertent mistake made early on by an Edison employee. During the initial investigation into the fire, in 2018, the employee turned over to investigators data that corresponded to Dec. 4, 2017 but did not provide any data for Dec. 5, 2017 — the actual day the fire started.

Edison found the time to fact-check a recent LA Times article about the Creek Fire federal complaint on January 31st (twelve days after they had found irregularities in their Eaton Canyon transmission lines and a week before they would report them). The company denies responsibility for both the fire and any evidence suppression.

“It is also disappointing to see the Los Angeles Times try to stretch the truth and draw parallels between the 2017 Creek Fire and the current wildfires,” they wrote. Will we ever stop disappointing this company?

There have been previous rodeos as well. Back in 1997, Cal Fire full-on raided SoCal Edison’s headquarters in Rosemead to seize documents related to a fire in Calabasas that SoCal Edison equipment was ultimately found to have caused.

In the clandestine operation, Cal Fire planted an investigator at the utility’s offices posing as an architecture student to draw up floor plans for the upcoming raid.

Cal Fire can carry out raids, it turns out. Imagine their mascot Captain Cal the Mountain Lion battering-rams your office door.

And the architecture student who you had let draw your floor plan for some reason is right behind him! You had even offered him a piece of the September birthdays cake!!

Whether or not they actually withheld evidence in any of these cases, you can see why even an enormous corporation might want to avoid being held responsible for a large and very destructive fire, especially when you look at some of the settlements SoCal Edison has negotiated just in the last few years.

In 2019, investigators found SoCal Edison equipment responsible for the 2017 Thomas Fire in Ventura and Santa Barbara counties, where two people died in the flames and then 23 more in the mudslides across the burn scar. SCE’s total payout for the Thomas Fire has been in the $2.7 billion range. The company has acknowledged no wrongdoing.

In 2020, investigators found SoCal Edison equipment responsible for starting the 2018 Woolsey Fire in LA and Ventura counties, which killed three people and burned 100,000 acres. The total payout for the Woolsey Fire has been about $5.4 billion. The company has acknowledged no wrongdoing.

In 2022 the company was forced to pay more than $400 MILLION DOLLARS IN DAMAGES TO ONE EMPLOYEE who said he was fired in retaliation for reporting sexual harassment by supervisors. The company has said they’re going to appeal.

The Eaton fire is projected to cost more than all of those losses put together — at least $10 billion.

Reading all this you might wonder if a city or state has ever taken control of a private utility’s assets. The answer is yes! It happened in the City of Los Angeles.

Drunk off Owens Valley water they had just aquired via a multi-year trickery campaign, William Mullholland’s Water Department wanted to get into the business of hydroelectric dams, and in 1912 got the City Council to start the process of buying out all of SoCal Edison’s equipment within city borders. The negotiations officially began in 1922 and ended fifteen years later. “Fortuitously for SCE, its loss of business in Los Angeles was quickly offset by suburban growth throughout the LA basin,” the company says on its Our History page.

Ventura County began looking at options for starting its own public utility to replace SoCal Edison last month, led by Supervisor Jeff Gorell, a Republican who used to work for Mayor Garcetti and does not care for SoCal Edison.

“It has become, certainly in the last couple years, an institution that I find to be unaccountable, arrogant, unresponsive, nontransparent, and at times, enacting questionable operational decisions.”

As of 2015, an LA Times study found that SoCal Edison clients were paying “way more” for the same amount of power than LADWP clients, part of a pattern of discrepancy between public and private utilities.

In Sacramento, a family using 500 kilowatt hours of electricity last October was charged $58. Customers in Los Angeles, also served by a public utility district, paid $79.

Pacific Gas & Electric charged $93 for the same amount of power. Southern California Edison billed customers $97. And San Diego Gas & Electric topped the Southern California Public Power Authority survey at $116 for 500 kilowatt hours.

Whatever the current gap is between LADWP and SoCal Edison rates, it is probably about to widen. Last Thursday state regulators approved SoCal Edison’s plan to hike rates in order to pay for $1.7 billion in damages from the Thomas Fire, with another rate hike plan for $5.4 billion in damages from the Woolsey Fire still on the table.

And that’s what’s going on with Southern California Edison!

2 questions: What happens if a public utility is found responsible for a fire? Would it bankrupt the municipality that owns it? A 3rd question: What is the estimated cost to bury transmission lines and would environmental protections even allow it?