How one corner of Hollywood could change, and why it won't

This is also what democracy looks like.

Right now, and only because it has to, the City of LA is going through the process of giving form to the built environment of its future. It does this by updating its housing element: the plan for how much housing is allowed on its land, and how many units it wants to see get built over an eight-year cycle.

The goal this time around is to build a lot more new housing. City governments in captivity only exhibit this behavior when distressed or when the state is making them — and this cycle, LA is required by new state laws to significantly increase its housing production. The city’s state-mandated goal is about 456,000 new units permitted between 2021 and 2029 — a huge jump from the last cycle’s goal of 82,000. And as part of this mandated process, the city has to change its own zoning by this February to accommodate 255,000 more units by the end of 2029.

So the city has been in the lab and came up with a zone change plan that it’s very proud of: the Citywide Housing Incentive Program (CHIP). CHIP is a combination of sub-programs that loosen zoning restrictions and encourage new housing in job-rich, transit-rich, and rich-rich parts of LA — particularly along major boulevards they’re calling Opportunity Corridors.

CHIP is going through the city legislative process right now. There’s a lot of fanfare around it, and broad agreement from elected and planning officials that LA is experiencing a major housing crisis that is driving our traffic crisis, homelessness crisis, out-migration crisis, worker shortage crisis, mass rent burden crisis, bad air quality crisis, etc., and we have to do something.

But if 255,000 new units by 2029 sounds unlikely, that’s because it is. Everyone involved in this housing element process knows it is going to fail. It’s designed to fail, in fact. LA’s leaders are choosing to develop a plan that will bring the city far, far short of its own housing goals. They are pointing at the bleachers, then setting up to bunt.

What’s the problem? First of all, the first third of this housing element cycle is almost halfway done, and only about 62,000 units were permitted in the first three years — with permits headed on a downward trajectory. That gives CHIP five years to violently reverse course and produce the required 255,000 more units. But a study released last week by UCLA’s Lewis Center found that CHIP would only produce about 160,000 new units over that time.

That’s because even though CHIP technically opens up enough new capacity for LA to meet its requirements, a lot of the potential new housing it supposedly generates is on lots that are unlikely to be developed — places where there are already new commercial or multifamily buildings, or where redevelopment doesn’t make financial sense for other reasons. So while CHIP would help generate significantly more units than the 117,000 that LA got permitted last cycle, it would not get the city even close to its goal for this one.

If LA actually wanted to meet its obligations, the UCLA report says, it would have to allow some apartments in areas currently zoned for single-family homes. “Failing to incorporate single-family parcels into its reforms will also delay progress on neighborhood desegregation and sustain rising rents and displacement of vulnerable households,” the report adds.

About 72% of developable land in LA is zoned for single-family homes. And yes, CHIP does not touch any of it. The first draft did include some single-family lots on the longlist for rezoning consideration, but then homeowner groups like United Neighbors — who exist to defend single-family neighborhoods and are very active in planning politics — immediately mobilized the troops. “If you’re not okay with the fact that a four- to six-story building can be built next to your house, you need to tell your elected official,” United Neighbors board member and CSI executive producer Cindy Chvatal told the Larchmont Chronicle at the time.

They did, and it worked. The final draft removed any zones changes to single-family neighborhoods. United Neighbors exchanged back-pats and declared their support to their email list:

“We know Draft #3 isn’t perfect. Will we see more density on our corridors? yes. But in our Community Plan meetings we can still advocate for each of our communities so this density makes sense in our community. What we managed to protect in this draft are: single-family, HPOZs/Historic districts, RSO, coastal and high fire areas. That took a lot of effort on all our part. It is important to get this draft passed.” (Bold and punctuation theirs).

But then, in an attachment to CHIP they called “Exhibit D,” LA City Planning included a few options for what upzoning some single-family blocks could look like. These options drew support from pro-housing groups like Abundant Housing and tenant advocate groups like SAJE and ACT-LA. They also drew a lot of opposition from United Neighbors and allied homeowners, who mounted another email organizing campaign to make sure no commission or committee took them up.

So far that campaign has been a thundering success. At the City Council’s Planning and Land Use Committee, the last stop before CHIP goes before the full Council, neither Exhibit D or any changes to single family zoning were even mentioned by its five members.

United Neighbors noticed. And as they often do when describing their own neighborhoods, they celebrated the peace and quiet in the committee to their list: “There was no discussion about adding single family neighborhoods among the committee members. And we realized that getting our letters out early to all the members was critical. Their minds weren’t being made up at the last minute.”

So what exactly are they so worried about? What do the options in Exhibit D look like?

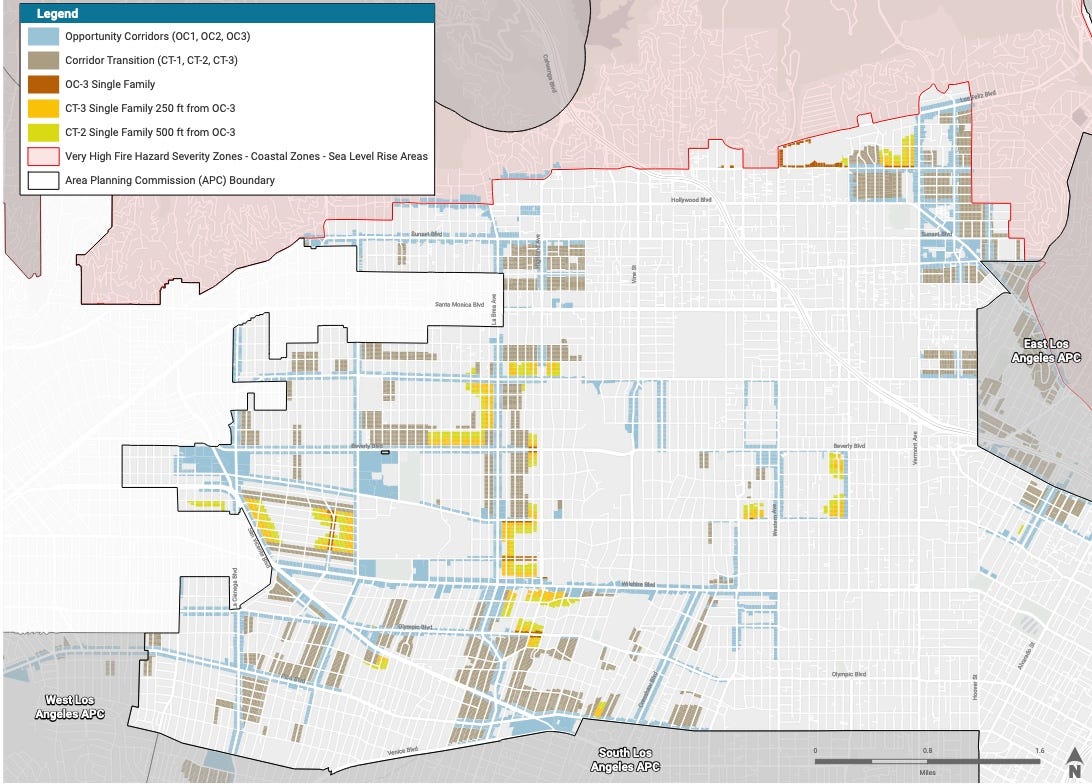

One option — Option 1 — would permit multifamily construction on every single-family lot in high-resource neighborhoods near transit. Here’s what that would look like in Central LA (Hollywood, Miracle Mile, Los Feliz).

The blue and grey are commercial/multifamily parcels on or near Opportunity Corridors — those are already being upzoned under CHIP. Koreatown and Westlake are untouched because they aren’t high-resource. But all those colorful patches are single-family lots in wealthier neighborhoods that would become eligible for two to seven-story apartment buildings. A technicolor dreamcoat of new multifamily zoning, enrobing The Grove, Museum Mile and the Wilshire Country Club.

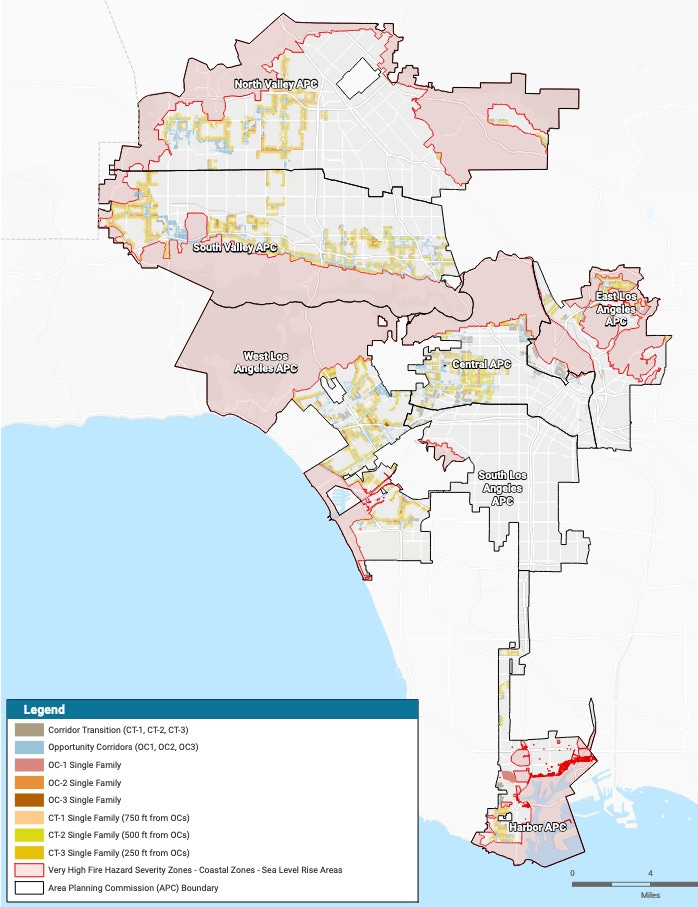

Here’s what it would look like citywide:

The UCLA study found that Option 1 would effectively double LA’s capacity for new housing. It would also likely spur the Hancock Park Homeowners Association to begin developing its nuclear program.

A much less aggressive approach — Option 3 — would add about a tenth of the new capacity of Option 1 and affect a much smaller number of single-family blocks, all within 500 feet of major transit stops within high-resource neighborhoods. Here’s what that looks like in that Central area:

Implementing Option 3 would not produce enough housing to get LA anywhere near its goal for this cycle. But even this option, the least obtrusive on the table, is far across the third rail for United Neighbors and its allies.

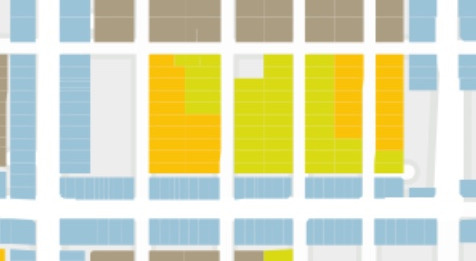

Last week I went to check out one four-block patch of single-family streets right next to Melrose Avenue that would open up to apartments under Option 3. Let’s zoom in on the patch:

The fat bookends are La Brea and Highland. In between are Sycamore, Orange, Mansfield and Citrus. According to the LA Times’s Mapping LA — a fun and ambitious project from 2009 that is now just a pile of dead links — this patch is actually a corner of Hollywood, because La Brea and Melrose are neighborhood borders.

There are about 70 homes in the patch (although some have ADUs). If maximally developed under Option 3, there could be somewhere around 550 units — up to three stories with ten units in the orange lots, two stories with six units in the green. (Full development takes decades or more likely doesn’t happen at all, so maybe 50 new units would get permitted by 2030).

That block of Sycamore already has apartment buildings on its west side — the strip of grey on the map. So a full implementation of Option 3 would basically make one side of the street look like the other. Here’s that part of Sycamore now, apartments on the right:

This is a sleepy little block surrounded by some wide awake corridors. It’s boxed in on one side by a transitional segment of the Melrose Zoomer Zone — Standing’s Butchery, Golden Apple Comics, Coffee for Sasquatch — and on the other by a cluster of businesses blessed as LA’s “coolest new hangout” by the Times last year — Sightglass, a Tartine. You can walk a couple blocks west to Pink’s and Best Buy on La Brea, or northeast to the towering fortress on Santa Monica and Highland — one of the old Bekins warehouses that look like relics of a medieval Storage Wars.

(In case I don’t get to talk about this again: Santa Monica and Highland is also the intersection where Sean Baker shot a lot of Tangerine, at the Happy Donuts that is now Trejo’s Donuts. That movie documents a just-bygone era when this part of Santa Monica was an Opportunity Corridor for the sex industry. A different director, the one who made Die Another Day, got busted there for propositioning an undercover LAPD officer in 2006.

The neighborhood has since been deemed investment-worthy, as has Baker. He has a billboard here for his new movie, currently the favorite at 15/2 to win Best Picture.)

Anyway. I walked a few blocks back to single-family Sycamore, then in a fit of ambition knocked on some doors to see what people thought about living next to an Opportunity Corridor, or if they knew they did. I introduced myself as an “independent journalist” and yet six people still talked to me — four on Sycamore and two on Orange.

One woman who had lived in her place for almost forty years walked me up and down the block and told me stories about the different houses. She was very hospitable to a large bebackpacked man invading her patio. Less so to the idea of more people living on her street.

When I brought up the prospect of her side of the block being legalized for ten-unit buildings, I got a head shake and tongue click. She told me that a while ago, she and some neighbors had fought to stop the owner of the auto body shop at the end of the street on Melrose from redeveloping his lot into a three-story apartment building. The concerns she raised were parking and privacy.

I mentioned that if her lot were upzoned her property values would go up. That got a disinterested shrug. But she was resigned that the body shop, its corridor opportuned, would probably get built up now. She asked me a few times if I was an “investor” but not in a mean way.

I didn’t have any other conversations with homeowners in the area, because nobody else I talked to owned their home. One woman was living with her elderly mother, who had owned the place for decades. The rest were renting. I was pretty surprised by the renter/owner ratio in the sample — there were a few For Lease signs up on other houses, too.

The non-owners were even less amenable to new apartments on the block than the owner. They also brought up parking and privacy, as well construction noise (some of them had kids). I didn’t bother mentioning that the value of the properties would go up, because that wouldn’t mean anything good for them.

And that was it. Nobody was all that animated about it, and nobody seemed to have been activated to stop it, but everyone I spoke to was broadly against legalizing new apartments on their block. And while I didn’t ask, my guess is that everyone I spoke to is an active voter registered at those addresses — a structural advantage they enjoy over anyone who would like to live in an apartment there someday.

The voting part is important. Because even under new state mandates, local elected officials have final say over the rezoning plans. United Neighbors is acutely aware of this dynamic: for their last push to keep CHIP’s tentacles out of single-family zones, they are organizing a letter-writing campaign to every member of the LA City Council.

Here’s how they assessed the Council's political balance to their list as we approach the final vote:

“We think the PLUM members will vote in favor again at City Council that would include Lee-Hutt-Yarouslavsky-Padilla. We think McOsker-Park-Rodriquez should also support. We aren’t sure of Blumenfield, Krekorian but most likely support. No idea about Harris-Dawson, Price. Hugo has stated support but could need more outreach, Raman-Hernandez are probably a no.”

To clarify: that’s nine members who, in their assessment, do NOT support any changes to single-family zoning. Then three unknowns and two who probably do. The two Councilmembers they have “no idea about” mostly represent low-income neighborhoods in South LA. And they’re right about “Raman-Hernandez”: in an unusual move, Councilmember Nithya Raman went to the Planning and Land Use Committee to speak in support of some of the options in Exhibit D, and Councilmember Eunisses Hernandez has already written in favor of the most-expansive Option 1.

But nine members are already more than they need. If they’re right, anyone concerned that the four blocks north of Melrose and east of La Brea will not remain a sanctuary for single-family homes can rest easy. One three-bedroom house is currently available to rent for $13,500 a month if you’re interested in moving in.

YIMBY is democracy?

Best part: “I introduced myself as an “independent journalist” and yet six people still talked to me — four on Sycamore and two on Orange.”

Fun to read about my old neighborhood—lived on Wilcox Pl, a one-block street between Lexington and Santa Monica 4 blocks east of Highland. Felt very cool living on the stretch where Tangerine had just been shot at the donut shop on one end, and On Cinema featured the Yoshinoya Beef Bowl on the other end.

Not surprised by the attitudes of the people living in single-family homes around there