One reason why there are tents on the sidewalk

A downtown hotel, a cash aid program, and a locked room with a dog inside.

On Saturday I went downtown to look at the St. George Hotel. I’d been reading about it in connection with a program called General Relief.

A couple of articles were going around last week — one by Patrick Fealey, who has been living in his car in Rhode Island for years, and one about a $1000 monthly grant experiment in Denver — that had gotten people talking about the effect of cash aid for people who are homeless.

Los Angeles has done a cash aid experiment of its own for almost a hundred years. That’s what General Relief is — a county program that gives a monthly grant to people who have nothing and can prove it.

All counties in California have been required by law to “relieve and support all incompetent, poor, indigent persons” since 1933 — meaning they have to offer some kind of financial assistance to their lowest-income residents. We’re the only big state with that requirement.

But every county has a lot of discretion over how much relief and support it wants to provide. San Francisco offers up to $687, but only $105 if the recipient is homeless. (That distinction was the work of Mayor Gavin Newsom. Under a 2002 program called “Care Not Cash,” he guaranteed all homeless program participants a shelter bed and docked the cost from their monthly grant.)

LA’s General Relief offers $221 a month. Here are the requirements to get that money:

You have to prove that your monthly income is lower than $221.

You can’t have a car worth more than $4,500 — unless you live in it, in which case it can be worth up to $11,500.

Your other possessions have to be worth less than $2,000 in total.

You can’t have more than $100 in cash or a bank account.

If you can work, you have to spend twenty hours a week in job training and can only stay on GR for nine months out of the year.

If you can’t work, you need to apply to get on federal Supplemental Security Income (SSI), at which point you’ll be kicked off GR.

You have to fill out a report to renew the payments every quarter.

You have to be a citizen or have a green card.

Even with all those requirements, there were 125,000 people in LA on General Relief last month. The program costs the County about $300 million a year.

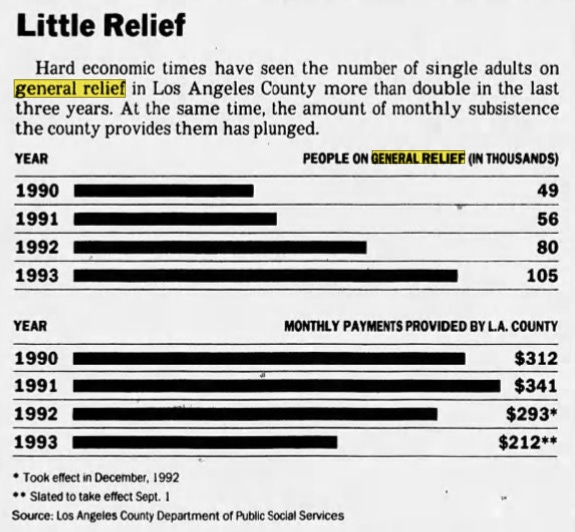

But here’s what’s interesting about GR payments: they used to be higher. A lot higher if you account for inflation.

In 1990, the monthly GR payment was $312. That’s $773 today.

For decades leading up to the nineties, you could find a lot of GR recipients in low-cost hotels in Skid Row. Mostly tiny dorm-style units with bathrooms on the hallway. In the early 90’s you could get a monthly rate at these hotels of about $250. A lot of people paid for their rooms using their General Relief money, with some left over.

One of those hotels was the St. George. It’s still there — right at 3rd and Main, on the edge of Skid Row but not in it. Two blocks from Grand Central Market, three blocks from City Hall.

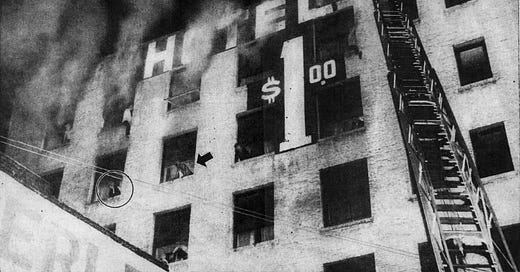

The St. George Hotel was built in 1904. In the early days it was popular with stage actors, because it was close to the Theater District. But over the next eighty years it was mainly famous for deadly fires.

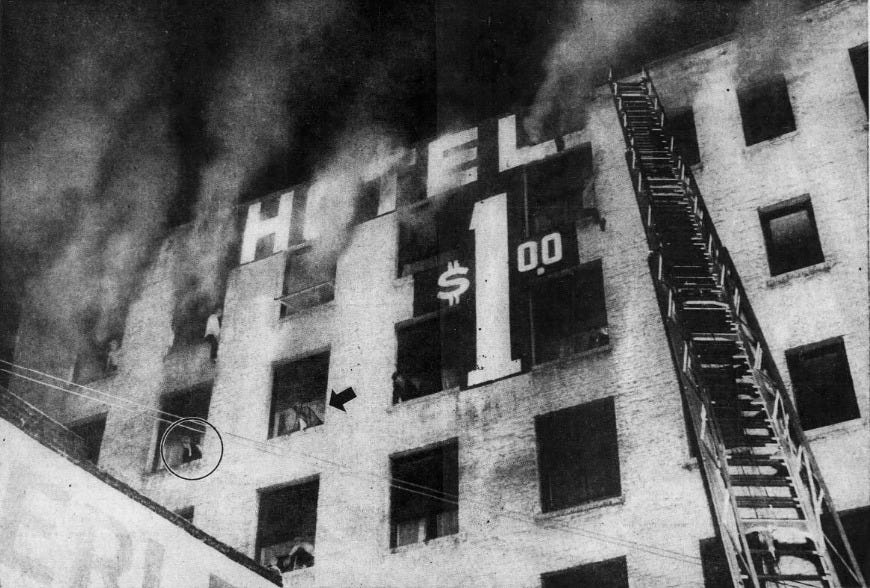

One fire killed six people in 1912. Another killed seven in 1952 — the story got space on the first three pages of the next day’s LA Times.

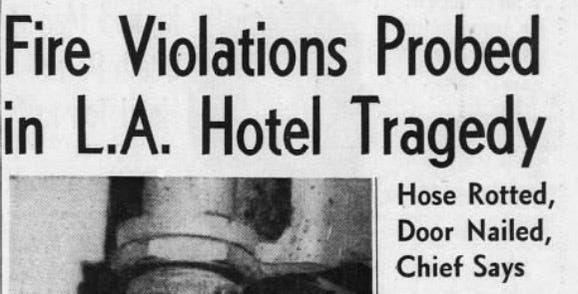

In 1982, the city cracked down on the St. George for being a prostitution den and brought a case against its owners, a Santa Barbara couple. A Superior Court Judge toured the building and called it a “time bomb” that he wouldn’t even send firefighters into if it went up in flames again. LA Times photographers who went with him found beer bottles on the fire hose and a cat screaming at them through a hole in the floor.

“I just don’t think a hotel that looks like that should be allowed to operate,” the judge said.

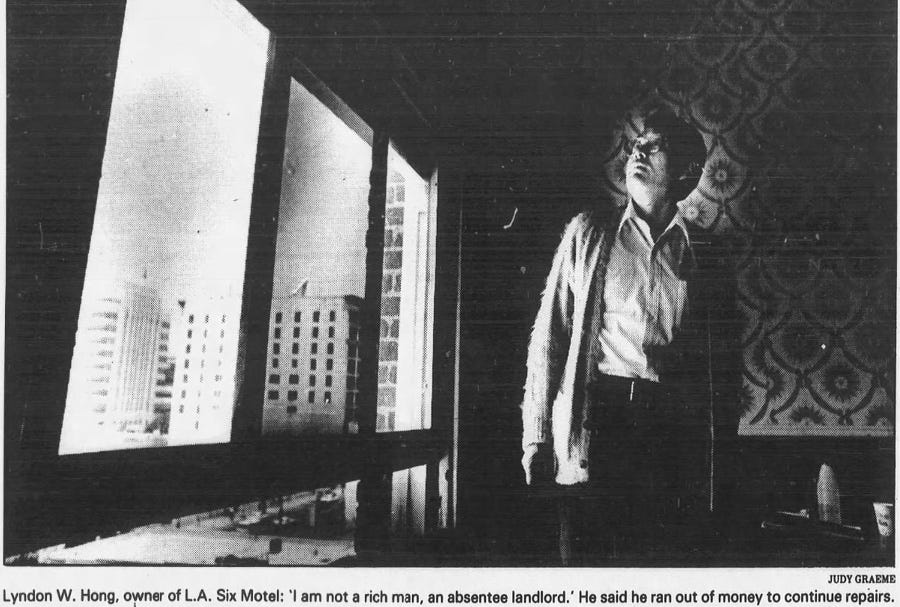

It was then sold for $400,000 to a Palos Verdes man named Lyndon Hong, who changed the name to the “L.A. Six Motel” — part of a rich tradition of LA businesses naming themselves to sound kind of like more successful businesses. There were families in the building at the time, including about 25 children.

Then there was another fire there in 1983. One man died. As the city prepared to bring charges against Hong, he said he’d spent all of his money and even sold his home to maintain the building, but still couldn’t afford repairs because he wouldn’t run it as a “house of prostitution.” “I am not such a man,” he said.

Then the County cut the monthly GR payments. First to $293, then to $212.

The County made the cuts to dig itself out of a budget crisis. General Relief was slashed by more than any other program. The vote by the Board of Supervisors was unanimous.

After the second cut, the manager of the St. George was quoted in the LA Times about how the changes had affected the business.

“John S. Hong, who manages the St. George Hotel on Skid Row, said he lowered rents last December to accommodate those hit by the county’s last reduction in general relief payments from $341 to $293. But this time, Hong said, the best he probably will be able to do is come up with a 25-day rate -- giving general relief recipients 25 days of shelter and five or six days of homelessness per month.”

This article is what got me interested in the hotel. Almost overnight, residents of the St. George and all the other Skid Row hotels went from spending about two-thirds of their GR check on a month of rent in a dangerous hotel to spending all of it for a few weeks — forcing them onto the street for a few days of every month.

In 2001, Lyndon Hong sold the building for $1.2 million. It was bought by a nonprofit — the Skid Row Housing Trust, which owned a large portfolio of SRO hotels downtown — for $1.2 million, and underwent a $9 million renovation in 2004. The next year an LA Times reporter wrote that it “could pass as a smart new hostelry catering to the trendy.” The year after that another reporter wrote that it “could pass for a trendy rehabbed loft building from the outside.”

When the St. George was bought by Skid Row Housing Trust, it stopped being a hotel where people could show up with cash and get a room for a night or a week. The building was now permanent supportive housing: the rooms were subsidized, there were services on site, and tenants were formerly homeless clients of case managers who helped them apply for residency. Rooms usually went to the highest-need people, according to a scoring system the County uses called the Vulnerability Index. But you could still find a lot of people on GR in these buildings — pretty much all residents were on some kind of benefits, and their rent was calculated as a fraction of their income.

Then last year the Skid Row Housing Trust imploded. The city put all of its buildings under receivership. Then 17 of them were sold in August for $10 million total to Leo Pustilnikov, a 38-year-old Beverly Hills developer who committed to maintaining them as affordable and supportive housing. The St. George was one of the 17.

I went to look at the St. George on Saturday. I had passed the building many times on my way from City Hall to get coffee at Tilt.

There was an anxious-looking guy carrying some takeout containers outside the door. He said he had gone to get some food from a local shelter, but then when he got back his keycard didn’t work — all of the locks are electronic, and they sometimes run out of batteries.

There were no front desk, security, or maintenance workers in the building, and wouldn’t be until Monday — two days away. Nobody to open his door for him. His dog and his phone were locked in the room.

Inside the hotel, there was another man in the lobby sitting in a chair next to a bag of grapes, staring into space. He had also been locked out of his room when he’d gone to get food, also because the lock battery had died.

There were numbers posted by the empty front desk for a “main office” and “maintenance emergency lockouts.” All the numbers were out of service. The emergency lockout number led to a message that just said “Goodbye!” and disconnected.

A few other tenants passed through the lobby, which had a sitting area, a small kitchen, and a bank of lockers with two microwaves on them.

The place was quiet except for the meditative thunks of the elevator door, which never stopped opening and closing.

The residents said that property managers representing the new ownership had told them that the entire building was about to close for repairs because of a black mold infestation. They would all have to find a new place during the closure, but nobody was given a timeline for when that would happen.

Some of the rooms upstairs were sealed off. Down in the basement there was another sealed-off room, this one marked “Microbial Hazard,” next to some plastic trash barrels full of water beneath a large hole in the ceiling.

One of the residents had worked with a case manager to look for new housing and had even gone to see an apartment, but then the next day he was told he didn’t qualify. At that point the case manager told him his best bet was to “alert the media.” He hadn’t done that yet.

All the residents were generally satisfied with the building and would keep living there if they could. They’d been there for at least a couple of years.

One had moved to the St. George in 2020 after living in a shelter. It was the first apartment his case managers showed him, but he was eager to move in because “everyone was dying in the shelter from COVID.” He was on GR and paid $56 a month while going to the job training program a few blocks away. Another had been in a shelter after living with his mother until she died. He was now on SSI, and said his rent had just been raised from $191 to $422. Everyone had grown up in LA.

They said security had been on site “sporadically.” During the week there was a maintenance worker and a front desk person who took rent payments, and on weekends and holidays there was nobody. Case managers had been coming once a week, but the residents had heard they wouldn’t be coming anymore. The LA Times has also reported cuts to security and janitorial staff by the new ownership at other former Skid Row Housing Trust buildings.

There were always employees on site when the St. George was a hotel. When the 1952 fire broke out, a staff member operated the switchboard to call all the rooms. In both the 1912 and 1952 fires, the elevator operators helped people escape and were celebrated in newspapers as heroes.

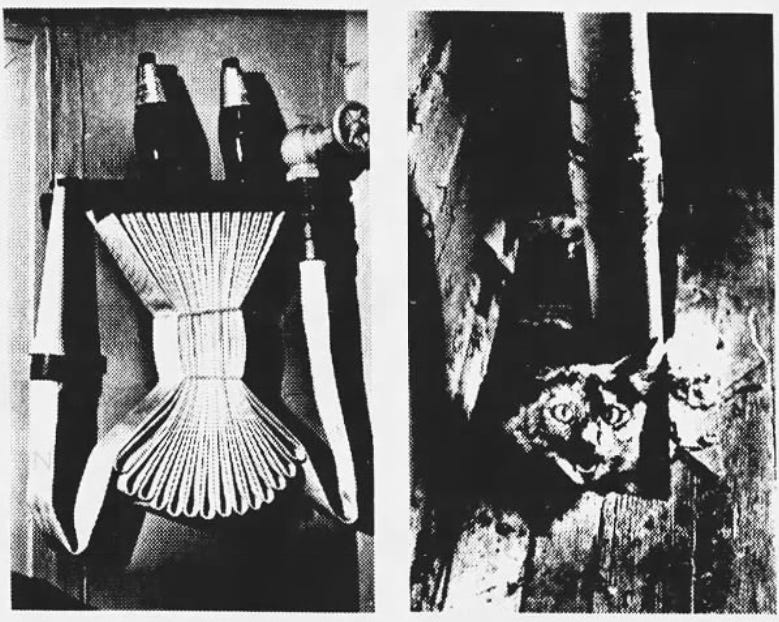

After the Skid Row Housing Trust first took the building over in 2006, the LA Times lauded the building’s on-site health services , including caseworkers, a psychiatrist, a doctor, a nurse, and a “medical examination room” in the basement.

This is what the medical examination room looks like now:

A downtown locksmith was able to come the building on a scooter about ten minutes after he picked up the phone. He used a little pump to make a gap in the bottom of the doorjamb, then ran a coat-hanger contraption underneath to pull down the handle while the dog barked at him from the other side. The cost for two doors was $150.

If you need one building to tell you the story of homelessness in LA, you could do worse than the St. George.

Skid Row flophouses and other cheap hotels around the city used to keep thousands of people off the street for a few dollars a night. General Relief got you an unsafe, unhealthy room for a month with money to spare.

Then the monthly payments were cut. The dollar amount hasn’t changed for thirty years, but its buying power has fallen steadily with inflation: $221 today would have been worth about $89 in 1990.

Meanwhile, many of the rooms got redeveloped into higher-end lofts. Others became supportive housing with higher barriers to entry. Then a lot of those rooms, due to mismanagement or an unsustainable model, fell into disrepair and were closed to tenants — like the St. George is about to be, at least for a while. In the 60’s there were about 15,000 SRO units on Skid Row. Today there are 7,000 and falling, most of which are supportive housing with diminished staff presence. Fewer dollars to spend, fewer buildings to get into, fewer people in the buildings that are left.

But a small tent is still $23.49 at Target.

This was great — as is the whole newsletter, thanks for starting it

The “Little Relief” source you included from DPSS is 🔥 I am trying to restack it but can’t figure it out 😕