The question nobody is going on TV about

Was the LA Fire Department underfunded, underdeployed, or something else we'll never know?

LA got a shoutout in Donald Trump’s inaugural address on Monday:

“Our country can no longer deliver basic services in times of emergency, as recently shown by the wonderful people of North Carolina being treated so badly, and other states who are still suffering from a hurricane that took place many months ago. Or more recently, Los Angeles, where we are watching fires still tragically burn from weeks ago without even a token of defense.

North Carolina got a nice applause break. Los Angeles did not. You want people to clap for a city that let fires tragically burn from weeks ago without even a token of defense?

That line in the speech was the culmination of a long-distance, high-velocity journey for a damning story: elected officials in the City of LA, particularly the Mayor, had so inhibited the city’s preparations against the fires as to be responsible for the death and destruction that ensued. (The County, which oversees the unincorporated community of Altadena, has not been subjected to this discourse to the same degree, maybe because it would take too long to figure out who’s in charge.)

The no-defense story first really got legs the night of January 7th, just a few hours after the Palisades Fire broke out. Most of the homes and businesses in the neighborhood were still in flames and Mayor Bass was on a plane back from Ghana. That was when Rick Caruso went on Fox 11.

“We’ve got a lot of tough questions that we need to ask the Mayor, and the City Council, and our representatives, and the County representatives — why didn’t you work to mitigate this? What was your brush mitigation program?”

You can hear the idea gaining momentum with every “mm-hmm” from the anchors. We were zeroing in. Elon Musk, a Caruso supporter during his 2022 campaign, picked up the brush clearance thread the next day.

Councilmember Traci Park, the representative for the Palisades and one of the Council’s most conservative members, grabbed the baton the morning after the fires. Having been implicated by Caruso as a member of the City Council, she took the opportunity to let everyone know this hadn’t happened on her watch, and she was just as mad at the actual perpetrators as you were.

“The chronic under-investment in the city of Los Angeles in our public infrastructure and our public safety partners was evident and on full display over the last 24 hours,” Park said. “I am extremely concerned about this.”

Chronic under-investment in our public safety partners. A new consensus on what went wrong was nudging brush clearance aside. The problem was actually that the Fire Department had been underfunded — specifically by Mayor Bass, who had cut the Fire Department’s budget by $17 million in the last budget.

The cuts immediately made international headlines, with plenty of interest across the political spectrum of your feed. LA Times owner Dr. Patrick Soon-Shiong, who had explicitly laid out his intention to make his paper more Republican well before the fires, tweeted about the cuts and went on Fox News to reaffirm that the destruction of the Palisades was a direct consequence.

“Now you see the end result of that devastation.” No question about cause and effect. You cut the Fire Department, you get fire.

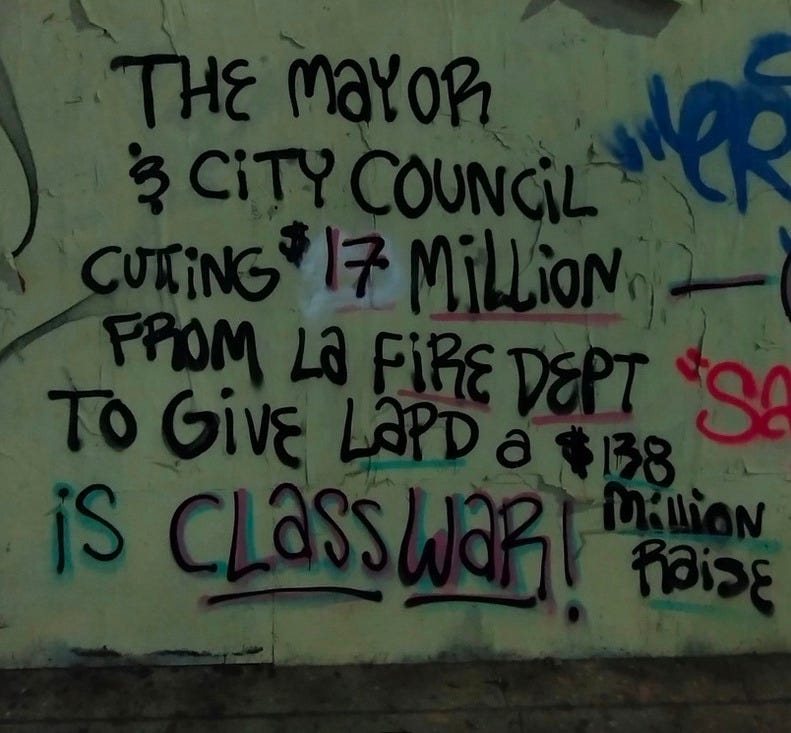

Where did the money that was cut from the Fire Department get spent? There was less agreement about that. Posters on the left, fueled by infographics created by City Controller Kenneth Mejia, said that the money had gone to an increase to the police budget — the department annually took the largest share of the city’s General Fund by far, and their budget had risen by more than $100 million the previous year. That allegation even showed up in graffiti, like expository context in a video game.

But obviously the police funding angle was not very useful to the right, who found other beneficiaries who had received the Fire Department’s resources. Donald Trump Jr. said it had gone to Ukraine. A Fox Business subheadline named “EV charging stations and DEI program” as the recipients. Traci Park, no less an authority than the City of Los Angeles’s representative to the Palisades, implied to the New York Post that the Fire Department’s money had been spent on crack pipes.

“We have gone so far away from core services,” she added. “We are spending a billion dollars a year for the homeless and what is it getting us? It gets us ‘harm reduction kits’ so we are basically handing out free crack pipes enabling people to stay addicted and out on the streets rather than fixing our sidewalks and investing in our fire department.”

Cop raises and crack pipes. But that was what was so satisfying about the budget cuts angle: you could point to any increment of $17 million of the many billions in the City’s budget and name it as the money stolen from the Fire Department, like the bills were marked.

And the causal connection between the cuts and the fires was clear — the Mayor’s budget had eliminated some vacant mechanic positions, so there weren’t enough staff to repair fire engines. Multiple news outlets shared aerial footage of the LAFD’s “boneyard” — damning footage of trucks blocked-in and moldering on a storage lot while neighborhoods were consumed.

The underfunding of the Fire Department became undeniable on January 10th. With the Palisades Fire still at 0% containment, LA Fire Chief Kristin Crowley went on NBC 4, Fox 11, CNN, and CBS all in one day to confirm what everyone had been saying: Mayor Bass’s cuts had hampered the Fire Department’s response and made the fires worse.

Crowley’s appearances were seen as a career kamikaze mission that would inevitably get her fired by a vengeful Mayor. But by going on TV, Crowley earned the support of United Firefighters of Los Angeles City (UFLAC), the politically powerful firefighter union. UFLAC had held Chief Crowley at arm’s length as recently as last year — an anonymous letter purportedly from current and former chief officers even claimed that the union had considered calling a no-confidence vote against her. But after her January 10th media tour, UFLAC leadership was with her “110%.”

“In the LAFD it went viral,” said Freddy Escobar, president of the United Firefighters of Los Angeles City, the union representing the department’s rank and file. “Everyone was very shocked, but very happy and excited. They support her 110%.”

“This is the only fire chief that has spoken up against the people who appointed her,” said Capt. Chuong Ho, another union leader. “If that doesn’t show courage, I don’t know what does.”

So the story was locked in. Traci Park and Kenneth Mejia, arguably the city electeds holding down opposite poles of the city political spectrum, were aligned that the Mayor’s underfunding of LAFD had contributed to the fires, and the Fire Chief was right there with them.

I was still working at City Hall during the last budget deliberations. What actually happened to the Fire Department is the same thing that happened to all the other departments: cuts were made to vacant positions in order to make room for salary increases for just about every employee.

Raises went to the police officer union (a $198 million hit to the 2024-2025 budget), to UFLAC ($76 million), and to the 24,000 members of the Coalition of City Unions ($206 million). One of the largest city unions celebrated the deals as “the largest raises in City of Los Angeles history.” The UFLAC raise wasn’t negotiated until after the budget process, but the money was held aside and delivered as planned, leading to an overall increase in the LAFD budget for the fiscal year. 1700 vacant positions were cut across the city.

I worked for City Councilmember Nithya Raman, who voted No on the budget, and helped design the office’s approach to that vote at the time. But the final budget passed 12-3. It wasn’t really all that controversial within City Hall, including among electeds who are now railing against it. Traci Park voted Yes.

As for the homelessness dollars, they do not go to “crack pipes” or harm reduction kits to any degree worth mentioning. Almost all the money for kits comes from County Public Health and state grants. The pipes inside some of the kits are meant to encourage fentanyl users to smoke rather than inject, in order to reduce disease transmission and overdose deaths (which are falling, some say because of harm reduction investments).

Where the vast majority of the city’s homelessness money actually goes is outreach, shelter, and housing programs — like Mayor Bass’s Inside Safe, which notably went to Traci Park’s district for its first highly-publicized intervention and transported 100 people out of one of the city’s wealthiest neighborhoods and into hotels in South LA, effectively resolving some of the most intractable political problems in Park’s district at huge expense within weeks of her swearing-in. At the time, Park was understandably on board with using homelessness dollars for this purpose:

"This initiative is to show that the Government can be a place to heal. We don't just want to say it; we want to show it. Putting people in rooms without the care they need doesn't work. We need to ensure that they have adequate access to services they need including mental health, trauma, and substance use services for the unhoused."

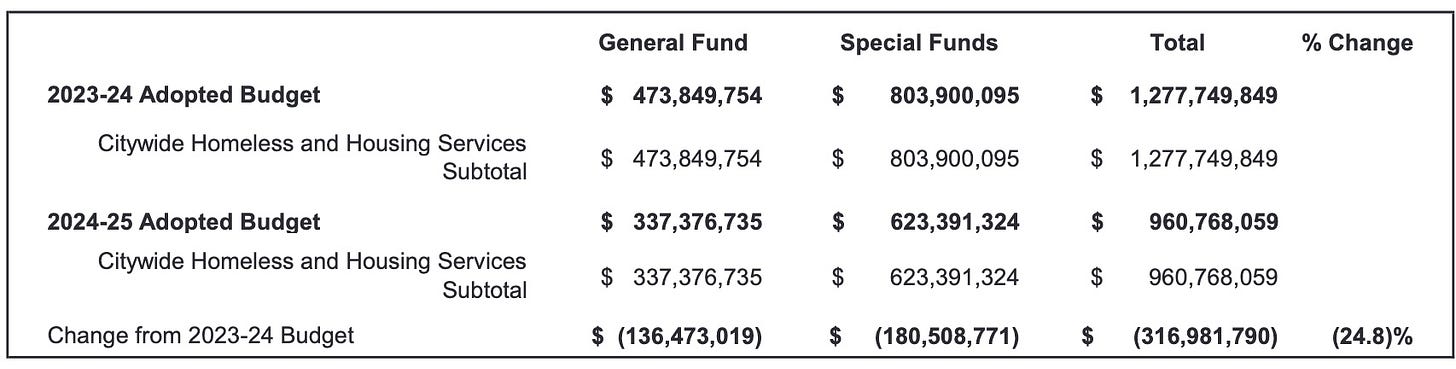

Homelessness expenditures, for what it’s worth, were also cut by $316 million in the same budget everyone is talking about.

But none of the details mattered except one: trucks were sitting in the boneyard while the city was on fire, and the Mayor had put them there. All of our tokens of defense had been locked in the garage. Bill Maher was sold.

Later in the episode, Maher interviewed Rick Caruso. A few days after that was Trump’s inaugural address. We’re probably going to hear more of the same when he comes to LA on Friday.

But a different, quieter question has been popping up. And it doesn’t exactly square with the campaign to blame the fire damage on budget cuts to the Fire Department.

A handful of LA Times reporters, led by Paul Pringle and Alene Tchekmedyian, have been looking into whether the Fire Department fully utilized the firefighting resources they did have.

As the Los Angeles Fire Department faced extraordinary warnings of life-threatening winds, top commanders decided not to assign for emergency deployment roughly 1,000 available firefighters and dozens of water-carrying engines in advance of the fire that destroyed much of the Pacific Palisades and continues to burn, interviews and internal LAFD records show.

Fire officials chose not to order the firefighters to remain on duty for a second shift last Tuesday as the winds were building — which would have doubled the personnel on hand — and staffed just five of more than 40 engines that are available to aid in battling wildfires, according to the records obtained by The Times, as well as interviews with LAFD officials and former chiefs with knowledge of city operations.

Was it not just broken trucks that were in the garage? Had fully operational trucks been held back from services, along with more than a third of the department’s firefighters?

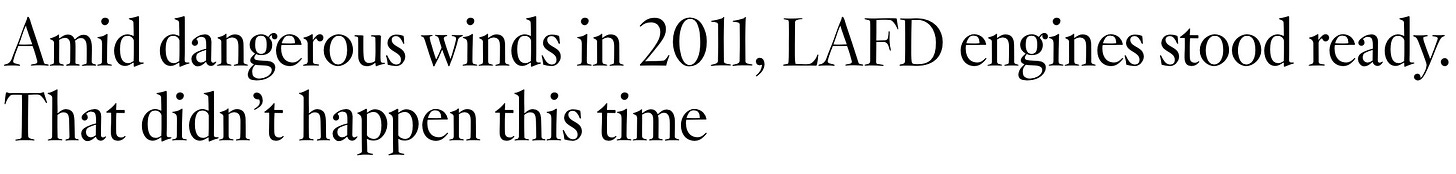

Keeping firefighters on duty and staffing “ready reserve” engines have traditionally been part of the preparation for high-wind events, according to the Times coverage. Both were part of the pre-deployment plan in December 2011, during the last comparable high-wind event in the city (even though those winds came with much lower fire risk, thanks to to an unusually rainy October and November that year).

And the Fire Department demonstrated that they were capable of executing a stronger pre-deployment plan last week. When the winds were predicted to pick up again, firefighters were kept on duty and ready reserve engines were staffed.

There has been a back-and-forth on the deployment question between the Times and the Fire Department. One thing is clear: somebody in the city is leaking about it.

An internal planning document obtained by The Times from a source showed that the department said “no” to deploying an additional nine engines, known as “ready reserve” engines, to fire-prone areas. Those are different from the nine engines that were pre-positioned in the Valley and Hollywood.

Crowley initially told The Times that most of the ready reserve engines were inoperable or otherwise unavailable. Later, however, a spokesperson for Crowley said just four of the nine were not immediately available. A third official then produced a document that said seven were put into service at one point or another — most of them after the fire ignited.

But the trajectory of the under-deployment story differs from the under-investment story in one major way: nobody seems to want to go and talk about it on TV. I haven’t seen any elected or city leader do a media hit on it. Caruso hasn’t brought it up. Chief Crowley didn’t even respond to inquiries from the Times about why the deployment on January 7th didn’t match the resources that had been sent out in 2011.

That may be because this story isn’t really helpful to anyone. Unlike the budget, where the Mayor can assume the blame (even from City Councilmembers who supported it at the time), pre-deployment is a widely shared responsibility. Dozens of people in leadership at the Mayor’s office, the Council offices, and the Fire Department itself could have made calls to ensure that every available LAFD resource was being utilized to protect high fire-risk neighborhoods. If it didn’t happen in the Palisades, does that mean nobody made the call for them?

But we still don’t really know if the Fire Department’s pre-deployment was below what it should have been. We don’t know to what degree the deployment was affected by cuts. And while the response time to the Palisades Fire was definitely longer than normal (21 minutes from the first 911 call to the first trucks showing up, compared to a department average of about seven), we don’t even know if more deployment would have allowed firefighters to stop the fire from spreading. We really don’t know if any decision related to the City of LA’s response was a contributing factor to the devastation wrought by the fires — again, the same thing happened in Altadena, which is not part of the City of LA or covered by its Fire Department.

And it’s unclear if we ever will know any of this. Getting answers to the pre-deployment questions would require the participation of at least some of the city leaders who have already gotten out there with a different, potentially conflicting premise. We haven’t seen a lot of willingness to walk back any assumptions so far. That might affect what we end up learning from this, or the policy changes we’re called to make.

If the City did leave working engines and firefighters out of service in advance of what the National Weather Service was calling a potentially life-threatening emergency, that certainly wouldn’t conflict with the Caruso/Trump premise of an underdefended city. But it might spread responsibility around to a degree that would unnerve some of those calling for the investigation.

Such a wonderful decision I made a couple years ago to never watch Bill Maher again. It's not that he's gone from being a liberal to being a conservative (I don't think that's true); it's that he's become a complete cynic who delights in undermining anyone on our (non-Trump) side. Tear your side down enough times and no one will believe in anyone.