WTF HAPPENED TO LOS ANGELES?!

Watching videos of people pointing at the places we used to go.

First of all: nobody is totally sure how it happened, but this newsletter is doing a LIVE FREAKING SHOW on Saturday March 1st at the Elysian Theater, co-produced with LA Forward. Here’s the poster by Julie Greiner:

The show: will be great. It’s about how LA works. Local comedians and elected officials, finally sharing a stage. Nobody is leaving until we figure out the whole “situation” here. For one night, the most powerful place in the city.

Tickets are $15 and all proceeds go to fire recovery. We’ll have a little party after at the theater. Right?????

Now: the normal newsletter.

*******************************************************************

The device I bought to prevent me from looking at social media doesn’t automatically restrict Youtube, so naturally I’ve been spending a lot more time there. Lately it has been serving me roughly ten billion videos a day about how LA is dying.

All the videos tend to go one of two ways: either a guy wanders around an epicenter of homelessness and talks to people who are on drugs, or a guy wanders around an expensive neighborhood and points at all the empty storefronts.

For some reason I’m particularly drawn to the pointing. I deliver a nice fat click every time the algorithm brings me one of these videos in its mouth.

Here’s a typical moment, from a pointing video titled “LOS ANGELES IS DYING! HOLLYWOOD & BEVERLY HILLS STORES GOING OUT OF BUSINESS! THE NEW SAN FRANCISCO?” The creator is named Money Hardaway. It has 683,000 views.

In what I hope is a measure of relief for Money Hardaway, there are still five more Cabo Cantina locations. Interestingly, as if pulled by a cosmic force, he happened to point at lot that previously occupied the most demented small business in LA history — a business so demented that to even begin addressing its dementedness would derail this entire post, so I’ll save it for the end.*

For what it’s worth, the former Cabo Cantina location is not entirely closed because of Hollywood dyingness. The building next door has plans to add some kind of crinkly office-digital billboard-restaurant designed by Eric Owen Moss. “The building becomes the sign, and vice-versa.”

But the causes obviously don’t matter as much as the clicks. Coverage of LA as an urban dystopia is algorithmically encouraged on Youtube, as part of a network of conspiratorial narratives that an artificial intelligence has determined drive the longest watchtimes and subsequently muscled onto all of our screens without even the gentlest human intervention at this point.

Still, that doesn’t mean the videos aren’t documenting something real. Businesses are closing beyond the pace that any single fire could cause, and commercial vacancies in LA are becoming an unignorable emergency — one with very far-reaching impacts on all of our lives here.

The epicenters of the disaster are in the core commercial centers. As of last year, Third Street Promenade was 25% vacant. There are dozens of empty storefronts along Melrose and Fairfax, once the national epicenters of hypebestiality. And barren, cavernous ground floors have become one of the defining characteristics of Downtown LA, driven by office vacancies that have hovered around 33% ever since the pandemic.

It’s tempting to not even bother looking for a root cause for why this is happening — there are plenty of obvious ones, and we keep hearing about them every time something closes. They include the pandemic, rising costs of food and labor, the Hollywood strikes, and a prevailing sense of decline. Zach Pollack, the chef/owner of Cosa Buona in Echo Park, announced its closure yesterday in an email to investors and namechecked everything on that list, including a vague allusion to problems in the neighborhood.

Cosa faced many of the same challenges as Alimento—covid, strikes, and sharply rising costs to name a few. But on top of those already hefty setbacks, that neighborhood took a sharp turn for the worse in 2020 and never recovered. When I signed our lease nine years ago, I made the mistake of forecasting that the neighborhood would continue to improve as it had in the years prior, but it is far worse today than it was a decade ago, which is really saying something.

There is always, inevitably some light dancing on the grave of restaurants like Cosa Buona. When it opened in 2017 with the name of the 50-year-old pizza place that had been evicted to make room for it, not everyone was happy, including the owners of the old pizza place. Just a few blocks down Sunset, Sage Regenerative Kitchen’s end was met with outright glee from vegans incensed by the restaurant’s expansion into animal-based offerings six months earlier.

But no business closure comes without compounding pain. We all intrinsically understand now that neighborhoods with less commercial activity are less safe and less healthy — conditions that lead to even fewer people on the street and more business closures. If Pollack’s “sharp turn for the worse” in Echo Park is a reference to the presence of homelessness and crime, neither of those is going to improve now that multiple prominent storefronts have locked their doors.

Still, even with an overabundance of explanations, there’s still something inexplicable about all these empty places. Such widespread, longstanding vacancy implies that there’s basically no demand at all for retail space in Los Angeles — not from entrepreneurs, not from massive corporate chains, not from mom-and-pop boutiques and restaurants. Is it possible that nobody wants to open a business right now?

Of course not. Someone would move into all these places at the right price. What’s happening is that asking rents are being held above demand. But how is that possible? Isn’t the market supposed to account for that? Why would landlords voluntarily make no money on a unit rather than lower rents to what the market will bear?

A working paper from the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard found one dominant explanation for long storefront vacancies: commercial landlords were holding out for a tenant who would offer the highest possible rent on the longest length of lease.

That would explain, to some extent, why single-operator shopping centers like the Westfield or Caruso malls haven’t seen the same level of vacancy as multi-owner corridors like the Third Street Promenade or Melrose Ave — the mall landlords are focused on the revenue of their entire complex, not just a single property, so they prioritize high occupancy rates to encourage foot traffic and ensure the financial sustainability of all of their tenants.

But even for single-building landlords, wouldn’t the prospective benefit of holding a retail space open run out pretty fast? At some point, a lower rent payment is better than none. It doesn’t explain why there are storefronts in places like Westwood Village that have been unoccupied for more than a decade.

I’ve also heard people mention that lowering rents can present an existential threat to building owners by violating their agreements with lenders, potentially leading to loans getting called back and affecting their entire capital structure. I’m following up with some building owners to find out how real a problem that is.

But to be honest, I haven’t found a satisfying answer yet — no really good explanation for why commercial rents are staying so high in what should be a tenant’s market, and therefore no good ideas for what could most effectively open store doors. Various cities are trying things: late in what turned out to be Mayor London Breed’s last term, San Francisco opened a program called Vacant to Vibrant, offering six months free rent to retail operations that would move into downtown. They’re claiming some level of success, and it’s probably worth trying in Downtown LA. But it won’t work by itself.

The truth, it seems, is that the street life will never come all the way back without a profound cultural shift that no policy tweak can bring about: the forcible resurrection of the in-person world. A mass going out of the way to put money and time back into conversational commerce, in defiance of the reality that all of the richest people on earth got that way from pulling us out of the world, and are now deploying their resources to expand the reach of its already-infinite alternatives, inspired by a techno-utopian totalitarianism that, as Emil DeRosa wrote yesterday, “reminds me of every guy I’ve ever met who’s afraid of the Big City.”

A few weeks ago, I saw a Reddit post about coffee shop culture in 90’s Los Angeles, and wondering what happened to it.

We used to hang out all night. Watch local music, poetry, art shows, game nights, community activism, etc. They were big, dimly lit, with cozy couches, local artists, paintings on the walls, and warm. Oh, and big ceramic mugs, not these tiny little paper or plastic cups.

After a late night at work in the late '90s we would hang out at various coffee shops till midnight two or three times a week. Now all coffee shops are tiny, stale, little hard-chaired, bright and cold shops that close before I get out of work. No community events and they just want you in and out.

The commenters offered up some helpful answers: it’s the rents, nightlife is all about alcohol now, work doesn’t end at 5pm anymore, there are still some good places in Koreatown. But I think the answer is probably in the question. Specifically the fact that the question was posed, responded to, and then consumed by me on the type of limitless, free discussion board where all of us go when we’re bored — the way people used to go to late-night coffeehouses. Platforms like Reddit, Instagram, and Netflix aren’t “third spaces.” They are first spaces. So that means the old third spaces are now, at best, fourth.

A while back my friend Bang Rodgman sent me this very charming remembered history of the Onyx Cafe, a coffeehouse that occupied the Cafe Figaro space on Vermont in Los Feliz until the turn of the millennium. The writer described it as a place that would gently eat your day.

Time was swallowed in a Vegas-like vortex. Ten minutes would melt into an hour, all night, your whole life.

But we have plenty of other ways to do that now, and we don’t have to drive to get there.

Unfortunately, our long, collective disappearance from street life has made it harder to get back to, especially with no omniscient algorithm to propel us there. But life in LA — and every place where part of the draw has always been how much there is going on — is going to get a lot less livable if we don’t try.

So where do we start? Experts agree on the most effective first step: coming to the live LA Power Hour show and party on Saturday, March 1st at the Elysian Theater in Echo Park.

*THE MOST DEMENTED SMALL BUSINESS IN LA HISTORY

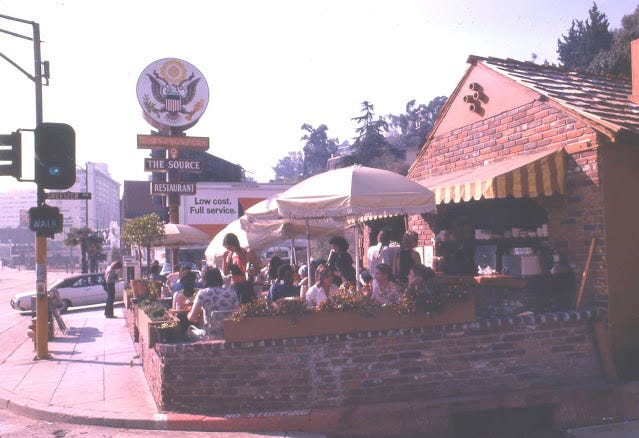

The previous occupant of the Cabo Cantina lot was The Source — arguably the restaurant that contributed the most to LA’s still-lingering association with weird people eating weird things for barely-intelligible health reasons.

The Source mostly served piles of vegetables, sometimes lightly dressed. There was an eggplant stuffed with olives and pine nuts on the menu known as “Mother’s Eggplant.” Woody Allen eats there in Annie Hall — he orders “the alfalfa sprouts and a plate of mashed yeast,” then runs over a garbage can in the parking lot because he is from New York.

The Source was owned by a guy from Ohio named James Baker, who moved to Topanga Canyon, killed his neighbor with a judo kick, somehow got away with it, opened a couple of health restaurants, killed the husband of a woman he probably slept with, somehow only did five months for that, convinced a guy on a hike to loan him $35,000 to open The Source, then changed his name to Father Yod and bought a mansion in Los Feliz where he could start a cult — the Source Family.

The mansion was formerly owned by Harry Chandler, the owner of the LA Times. Father Yod called it the Mother House and moved about 150 disciples there, including thirteen “wives.”

Baker died when he tried to go hang gliding without any form of lesson. Read all about it from Hadley Meares in LAist or watch the movie.

Feeling more and more that as a society we need to touch grass.

I moved to LA just in time for the last year of the Onyx. It wasn't a bad walk from our place around the corner from Jumbo's Clown Room, and gave rise to my ex's and my shorthand for a certain style of coffeeshop painting, "alien penis art".