Thank you to the Big City Heat family who came to (and sold out) the live show last week. What a hoot!!

Things are trending in the direction of doing more shows. My plan is also to put the video from this last show up here someday.

ON TO BUSINESS

A few things that happened since the last post:

On February 21st, Mayor Bass demoted Fire Chief Crowley. (Not “fired” exactly, because Crowley still has a job at the Fire Department. But basically she was fired. Some also like to use the word ousted.)

Crowley appealed her demotion, a pretty big move that forced the City Council to vote on her ousting. She argued that she’d been dismissed by Mayor Bass for going on TV and telling the truth about the Fire Department’s chronic underfunding, and how that underfunding was exacerbated by cuts the Mayor herself made.

On Tuesday, the City Council upheld Crowley’s demotion with a 13-2 vote.

There’s some SPECULATION out there that Crowley’s appeal, in the face of very unlikely odds, was a signal that she’s eventually going to end up suing the city. (Because in order to sue she’d need to credibly argue that she’d exercised all other options). A lawsuit like that would likely end up in a settlement for Crowley. That settlement would come out of the city’s General Fund, which includes the budget for the Fire Department — the one that, again, Crowley and many others have been saying is underfunded.

Let’s really chow down on some beefy LAFD underfunding discourse today. Not the defunding discourse, about whether Mayor Bass cut the Fire Department’s budget — I wrote about that already and so did ten thousand other people. Today we’re specifically talking about the underfunding issue — the contention that the Fire Department has been insufficiently staffed to serve the needs of the city for at least a decade.

There’s broad agreement in LA City Government that the Fire Department isn’t funded or staffed properly. But there’s somewhat less agreement on what the problem is or what to do about it.

In the aftermath of the fires, two reports about the Fire Department’s funding situation have been circulating inside LA City Hall. These reports, despite the fact that both share the same fundamental conclusion, are totally at odds with each other. One was actually written in retaliation against the first. And the story of these dueling reports is also a neat little fable about how the delivery of lifesaving emergency services in a city can get just as political as everything else.

THE DEAL WITH FIRE DEPARTMENT STAFFING

The math of Fire Department understaffing is not complicated: in the last 50+ years, calls for service have spiked dramatically while the number of firefighters has barely changed at all. In 1969, firefighters responded to roughly 100,000 calls for service. Last year they responded to half a million. Five times the calls, one times the responders.

But why did the spike happen? Why have calls for service gone up so far beyond the rate of increase in LA’s population since 1969?

To understand that, you have to understand a dynamic that’s pretty specific to LA: all of the city’s paramedics are firefighters. As in, they are employed by the Fire Department, they went to the fire academy to train in firefighting, they are in the firefighters union and their job title is “Firefighter.” Our paramedics are firefighters who specialize in emergency medicine.

Most other cities do things differently. In New York, emergency medical services are overseen by the fire department, but the paramedics are not firefighters — different job titles, different unions, etc. Chicago and San Francisco have some firefighter/paramedics, but also some paramedics who are not firefighters. LA, Phoenix and Houston sit at the far end of the “dual role” spectrum, where pretty much all the paramedics those cities deploy are firefighters.

Why is it like that, though? And when did it start?

LOS ANGELES IS PART OF PARAMEDICAL HISTORY

LA firefighters started responding to paramedic calls in (Bryan Adams voice) the summer of ‘69 (actually the winter).

That’s why 1969 is always the year cited as the beginning of the period when the department’s call volume started to spike. That year, firefighters took on a huge new responsibility — and it wasn’t just new for them.

Paramedic services are a relatively recent innovation in the US, especially outside of a battlefield scenario. Before the late 60’s, ambulances would pick up patients and bring them to the hospital, but wouldn’t do much to keep them alive at the scene or on the way. LA, in fact, was one of the first cities in America to deploy paramedics — just a few months after Columbus, Ohio, the city that pretty much developed the modern approach to American paramedicine, also in 1969.

In the first half of the 20th century, LA ambulances were mostly operated by private contractors. In the 40s and 50s, the LAPD deployed a small fleet of its own medical cars to transport patients and sit nurses on the wheel well.

But in 1969, LA cardiologist Dr. Walter Graf pioneered the “heart car”: an ambulance with actual medical equipment inside, the first of its kind on the West Coast. Local governments immediately got to work on providing the cars as a public service — but maybe because LA was an early adopter, officials looked to plug paramedics into existing services rather than create whole new ones. Fire departments were a natural fit to start rolling the cars out — they were already connected to emergency dispatch, and the number of fires had been going down for decades thanks to better building codes, so they might have had some extra capacity.

By December 1969, LA County Fire had a full-blown paramedic unit in service, and LAFD started deploying paramedics by the end of 1970.

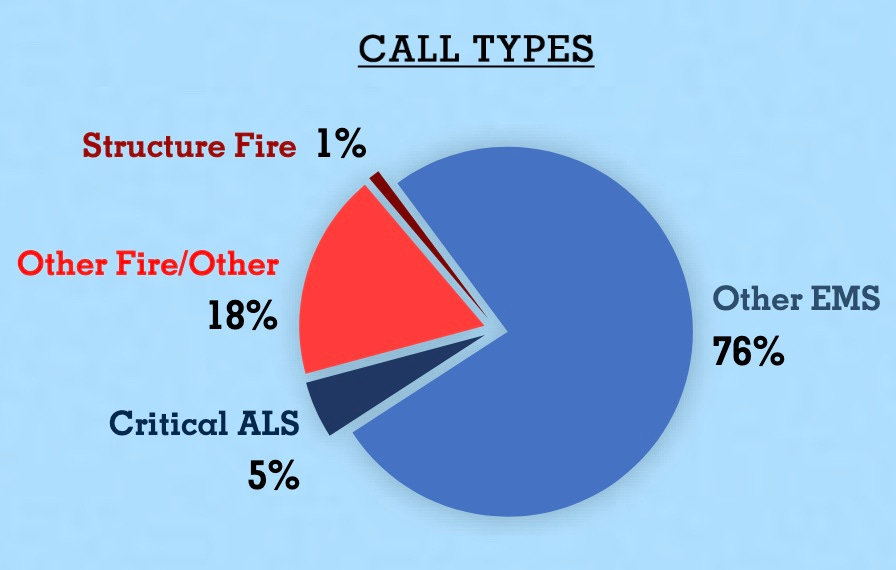

Fifty-five years later, the LA Fire Department is now primarily a paramedic response agency. Non-critical medical issues, in particular, make up the vast majority of the Fire Department’s calls.

ALS stands for Advanced Life Support for patients who need to be stabilized and monitored in the ambulance. So that means about 375,000 of the Fire Department’s 500,000 annual calls are for medical issues where the patient is either driven to a hospital without requiring significant medical attention or not transported at all (a little under half of all medical calls don’t result in a transport).

Some of the patients in these non-critical medical calls still require medical attention. But some do not. Many of them are 14-year-olds who did edibles and believe they have already died like Maureen Dowd, or people with chest pain that feels like a fatal heart attack but is actually just normal gas from some of LA’s most iconic foods. (Maybe a coincidence, but the Oki-Dog showed up not that long after LA deployed paramedics).

The department used to try to screen out these calls, but after a lawsuit over a 1987 call when LAFD initially didn’t dispatch help for a woman who was actually having a heart attack, they now respond to everything.

“I’ve gone out on hangnails, ingrown toenails and mosquito bites,” said Ron Lingo, a Fire Department paramedic who responded a few months ago to a call from a young mother concerned because her “baby hadn’t smiled for an hour.”

Today, there is no question that these non-critical calls are dangerously stretching the Fire Department’s resources. That brings us to the two reports.

THE FIRST REPORT

A third-party firm called Citygate wrote a report in 2023, commissioned by LAFD, on the department’s “Standards of Cover” — how successfully or not the department was meeting the city’s emergency needs.

The whole thing is worth skimming. But the big headline was that LAFD did not have the resources to meet the rising demand.

The report found that call volume at the department’s busiest stations was “the highest Citygate has measured in a metro client,” and call-to-arrival response times were longer than what they needed to be: an average of about nine minutes and twenty seconds, compared to a best-practice goal of seven minutes and thirty seconds.

The Citygate report had a topline recommendation for what to do about the capacity issue: hire some non-firefighters to respond to some non-critical medical calls, allowing firefighters to focus on higher level emergencies (like fires).

Here’s an excerpt that lays it out:

All incidents do not need the response of a paramedic firefighter engine, truck company, and/or a two-person paramedic or EMT ambulance for a ride to an emergency room. LAFD is well-suited to be an alternative human crisis response agency with specialized responders in addition to LAFD’s firefighters. While such an alternative response system is needed Citywide, it is critically needed now in core eastern and southern City areas. Although constructing such a system represents a new expense, overall, it will be more cost-effective than adding fire units. The City “needs its fire department capacity back.”

The report cited some alternative response pilots implemented by the City and County in 2021 and 2022, but described them as “not enough.”

“The alternative response program needs to scale massively and quickly to lower the workload placed on fire units back down to moderate and serious emergencies.”

They also suggested adding some new firefighter-staffed ambulance units in the short term, as well one new fire station in the North Valley.

This report may not sound radioactively controversial. But it was. Especially to the union for rank-and-file firefighters, United Firefighters of Los Angeles City (UFLAC). UFLAC’s core principle is that LA needs more firefighters. So an alternative response program of non-firefighters, which Citygate said was “critically needed,” is not a suggestion they care to hear.

So this past December, a year after the Citygate report, the union put out their own Standards of Cover report in response.

THE SECOND REPORT

The UFLAC report agreed with the Citygate report that LAFD needed more stations and more staff, but disagreed on the numbers. Instead of the one new station recommended by Citygate, UFLAC recommended SIXTY-TWO.

Their report also suggested hiring many more firefighters. It did not, however, support a non-firefighter alternative response program.

Today, in the aftermath of one of the worst fire disasters in American history and the beforemath of another major shortfall in the city budget, many paths to addressing fire department capacity are being considered — with particular focus on the need for new facilities. The City Council is currently developing a bond measure that would pay for station repairs and construction of some yet-to-be-decided number of new stations. Definitely less than sixty-two, but probably a few more than one.

However, despite the Citygate report’s “critical” recommendation, the move to develop non-firefighter response isn’t really being explored anywhere. That’s because nobody in LA government has much appetite to go up against the firefighter union right now.

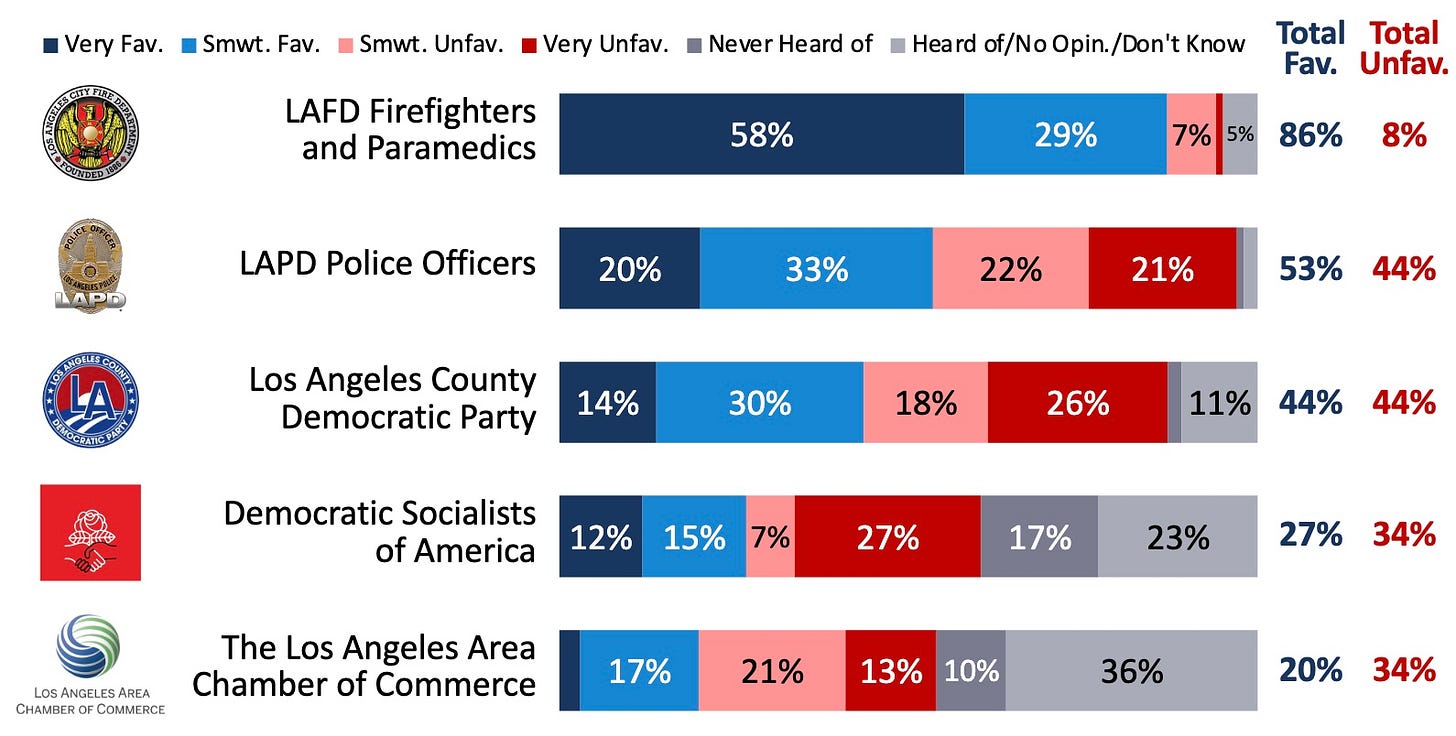

UFLAC was already a force in city politics before the fires. One big reason why: whenever anyone runs a favorability poll on institutions in the city, firefighters have always been near the top.

“I like firefighters” doesn’t necessarily equate to “I rely on firefighters to tell me how to vote,” but candidates still look at that data and conclude that the union’s endorsement carries extra weight. And you don’t need to commission a poll to know that those LAFD favorables have gone even higher since January.

The other big driver of UFLAC’s influence: they spend a lot of money on elections.

Just in the last few years of City Council elections, they spent almost $300,000 in PAC money to support Traci Park in 2022, $200,000 on Imelda Padilla in 2023, and $300,000 on Ethan Weaver’s campaign against incumbent Councilmember Nithya Raman in 2024. I worked on the Raman campaign, and can say from experience that going up against firefighter money probably feels something like riding in the back of a 1940s LAPD ambulance.

UFLAC also supported Rick Caruso in the 2022 mayoral election. Mayor Bass has made an effort to build a friendly relationship with the union, in particular by delivering its members a substantial raise last year. But that effort was undermined by her ousting of Chief Crowley, to whom the union offered its full-throated support after she went on TV to say that the city had failed the Fire Department due to cuts and underfunding. That means the Mayor now risks the firefighters supporting an opponent again in her upcoming re-election (like Monica Rodriguez, one of the two City Councilmembers who voted in favor of Crowley’s appeal and an increasingly likely mayoral candidate).

So this is the political filter through which LA’s approach to emergency services must flow. Every elected in the city agrees that the Fire Department is understaffed. But if any of them make the case that it’s poorly staffed, they might wake up to a few hundred thousand dollars worth of attack ads on their pillow.

Some more numbers: the American Heart Association says that your chance of survival during a heart attack decreases by 10% every minute without CPR or defibrillation.

BIG CITY ELITE

“Your emails are not long enough,” everyone has been saying. Here are a few good things I tried recently.

The cajeta latte at De La Tierra Cafe in East Hollywood

It turns out I had been needing a nice coffee shop just up Vermont from the Vermont/Santa Monica Red Line Station to solve most of my problems. Cajeta is like caramel except it’s made from goat’s milk. The drink is sweet and smoky with a noticeable but not onerous goat fonk. Good pressed breakfast sandwich too.

The blackened catfish at Stevie’s Creole Cafe in Mid City

I stopped here last week after a funeral in Rancho Park. Not sure if I’d heard of it before but their Instagram shows that Andre 3000 ate there 261 weeks ago and brought his custom double flute. The catfish: yowza. Big spice and juicy fatness like a rotisserie chicken. There are a lot of sides. I got coleslaw and banana cornbread, but if I had to do it again I might try the red pepper cabbage instead of the coleslaw. The cups of butter have a secret peach cobbler in the bottom. I did have some trouble deciding whether this section of Pico is colloquially part of the greater “Mid-Wilshire” or “Mid City” — it’s technically in Wilshire Vista, which Eric Brightwell did a nice writeup on in 2018.

The “Reframing Dioramas” exhibit at the Natural History Museum.

A live-in associate of mine demands to go to the Natural History Museum every weekend because she is obsessed with Professor Percy Pelican despite being scared to push the button that makes him talk. The Reframing Dioramas exhibit, on display until September as part of Pacific Standard Time, is just around the corner from Percy Pelican and the Bird Hall. It’s… so good? Trippy animated dioramas by local artists, normal-looking dioramas with placards explaining why they are actually fraudulent, and a lot of questions about whether arranging stuffed animal corpses behind glass is good or bad for animals. The exhibit has so many ideas. We’ve been four or five times now I discover something new and memorable every time (in part because after five minutes we need to go see the bugs).

Digging into a poll I hadn’t seen from January of 2024 is probably not a good use of my time, but the 2024 ThriveLA poll data was eye opening. I guess I was surprised how Dems support was low and DSA was even lower, but I guess the 2024 election seemed to confirm some of this. Weird how little info there is on the methodology on ThriveLA’s site and a slide show I found. I could not find any info on sample size nor margin of error, but their other polls seem to have about a 3.5% margin of error. Looks like FM3 conducted the poll and is seen as left leaning and has a C/D grade predictive rating from Nate Silver (for what that’s worth in 2025). ThriveLA funding the poll has me wondering how this balances it all out🤔

"the cups of butter" lmao. do another show! sorry I missed it.