Violent crime is down. Why are so many people mad about it?

And why is nobody coming to the table with real solutions for me being sick?

Good morning!

Sorry if this one is a bit sloppy. I got the flu and my sinuses have developed tides. Sometimes they swell and threaten the neighboring village, sometimes there are a bunch of barnacles and little crabs running around.

But hey, good news about something that rhymes with tides: homicides! They’re down!

Mayor Bass and Chief McDonnell rolled into the Watts Labor Community Action Committee this week and stuffed a huge number of people behind a microphone to do a press conference about it.

The numbers are nothing to sneeze at, especially if you have the flu and if you sneezed on your laptop you would have to throw it out. Homicides are down 19% from last year at this time, 25% from two years ago. LA had fewer than 300 homicides every year from 2010-2019, and barring a very bad couple of weeks we are going to be back there again.

Possibly a bit more complicated is why all this happened. The press conference credited “LAPD-led initiatives and community-based strategies.” But we have to account for the fact that approximately this same reduction happened everywhere.

Take a look at this report from the Major Cities Chiefs Association.

Of 69 reporting big-city police agencies, 58 saw a drop in homicides through the end of September.

Most of the 11 that went up were smaller cities and the change was essentially flat.

The overall change was an 18% drop in one year — almost exactly the same as LA’s.

But it turns out that the fundamental cause behind this trend is actually not that complicated at all. Violent crime spiked in every big American city during the pandemic. Then places reopened and a semblance of normal societal function resumed, and now violent crime rates are gradually falling back to where they were in 2019. Current LAPD reports show that every reported crime category is coming in below 2023’s year-to-date totals.

But like everything else, nobody can really agree on whether the reduction is even happening. The simple up-or-down trajectory of crime has been loudly, angrily sucked into the culture war, like a guy with the flu trying to get a single oxygen molecule into his nose.

If you read Instagram or X replies, you will often hear that crime is actually up, it’s just that reporting is down because crime is so high that people have given up on even calling the police. If you talked to Donald Trump during his campaign, he would tell you that FBI crime reports are “fake numbers.” And if you talked to Nathan Hochman during his own successful DA campaign, and you asked him how safe he feels walking around Los Angeles on a scale of one to ten, he would say “zero.”

There are plenty of other variations. One that implements and expands on the Instagram reply theory comes from Mike Gatto, a Democratic former state Assemblymember from Silver Lake and an increasingly visible commentator arguing that California Democrats have gone too far left and the state must implement “common sense” approaches to crime and homelessness. He did an interview with the Epoch Times where he said that “crime statistics lie” because “it’s only when they are actually convicted or they take a plea that that becomes a crime statistic.”

You might watch this video and think “that sounds wrong.” And you would be correct. Crimes become crime statistics when police file a report — no arrest or charge and definitely no conviction are required. “This is the most important thing that I want the viewers to understand,” he says before saying this extremely wrong thing.

Obviously not every crime gets reported. But crime data is useful for making year-to-year comparisons… and there is no evidence that crime numbers going down means crime is actually up. Meanwhile, none of this applies to serious crimes like homicide. If you discovered a body in your bedroom, which if you’re like me is wallpapered with a thick layer of snot, you would probably call the police even if you thought they might not show up for 20 minutes.

So why? Why this concerted effort to act like the falling violent crime isn’t falling? Especially when a lot of these people could easily use the crime numbers to lend credence to the conservative position that COVID lockdowns caused more harm than good?

You’re like, duh. These people are trying to win elections. Hochman was running against a progressive incumbent DA. You obviously can’t concede that anything good is happening when you’re running against an incumbent, especially when your main argument is that crime is spiking out of control. Gatto was one of the loudest spokespeople for Prop 36, the tough on crime ballot measure, and has more than $2 million in a 2026 Lieutenant Governor campaign account.

But another possible explanation might come from a more hidden place: many of these candidates and commenters have also invested a lot of opinion-having capital in the premise that a full-strength police force is the only way to bring down crime, and these reductions in violent crime are difficult to reconcile with that claim because in the vast majority of cities in the US they have coincided with a profound shrinking of officer staff, for which these same voices have also been criticizing leadership. Including and maybe even especially in LA.

It has been an article of faith in LA politics for decades that the city needs a lot more officers to make communities safer. In 1989, then-Councilmember Zev Yaroslavsky was one of the first to propose an increase to 10,000 LAPD officers. Later, Mayor Villaraigosa made the 10,000 figure one of his signature campaign pledges, and was finally able to accomplish it by shifting a few dozen officers from General Services Division to LAPD — basically making some city employees change clothes. But by the end of that same year the numbers were falling again.

Meanwhile, Zev Yaroslavsky admitted he had just picked the 10,000 officer figure because it sounded good.

The 10,000 figure lacked any analytical underpinning but was “a nice round number,” Yaroslavsky chuckled in an interview. It also “takes the force from four digits to five digits.”

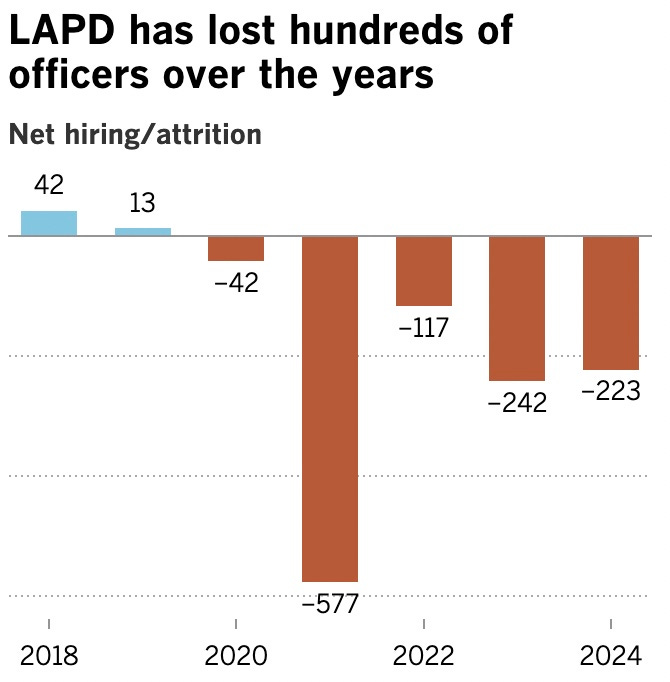

The staffing total hovered a little below 10,000 officers for about eight years, while the overall increase in officer numbers was widely credited for a steady decline in crime throughout the 2010s. But then in 2020 — as in most big-city police departments and almost every LA city department — LAPD staffing began to crash.

Both 2022 mayoral candidates ran on stopping the outflow, as I have campaigned on for my own respiratory system and with similar results. Karen Bass proposed maintaining the department at its current staffing level, bringing net hiring back up to zero. Rick Caruso promised to not only to make up all of the shortfall but somehow increase staffing to 11,000. How he would have attempted to do that remains a mystery for now, but without unprecedented revenue growth it would have required enormous cuts to other departments and city services.

But officer numbers kept falling after the election. Then in 2023, with the stated goal of improving recruitment and retention, now-Mayor Bass and 12 members of the LA City Council passed an increase to LAPD officer salaries that would amount to a $1 billion hit to the city budget over the next four years.

It didn’t stop the bleeding (there’s some blood involved for me as well).

When the raise was passed, there were about 9,034 officers. There are now 8,784. That means even after having implemented a hugely generous salary increase for both new recruits and veteran officers, LAPD is going to lose even more officers this year than it did last year.

The trend is not changing direction anytime soon. New academy classes aren’t even close to replacement level. Each class has a capacity for 60 recruits, which is roughly what’s required to make up for attrition in the force. But in April the LA Times found that the average size of the previous ten classes was about 30 — half full, a fraction that my nasal cavity left behind several days ago.

The most recent classes have been even thinner: the last class only had 20. The one before that had 21. Before that: 17. How about before that: 22. That’s an average of 20 over the last four classes.

Police budget increases have, in a way, functioned as a preventive measure against adding officers: cities like LA no longer have the financial flexibility to significantly expand the force even if we could. As the force has declined, spending has exploded with the new salaries, contributing to a deep budget deficit that has already forced the city to cut services, reach deeper into its reserve fund, and issue bonds to cover the gaps.

This is the one thing that’s always surprised me about how we talk about police funding: both sides of the debate seem to believe that the money goes to putting more officers on the street or adding resources in some way. But the vast, vast majority of it does not. It goes to higher salaries for officers. Not more officers — the same number, or usually fewer. Just making more money. This is how it works everywhere.

Anyway, back to what we were talking about: none of this appears to be having much of an impact on crime. It’s widely assumed that some unknown number of officers represents a threshold of police incapacity that, if fallen below, would unleash crime and violence — like the mystery amount of ginger ale for a flu victim that crosses the line from helping to hurting. LA has lost 1,100 fewer officers since 2020, and we have yet to reach that threshold. But if there is one, we’re going to get closer to it next year.

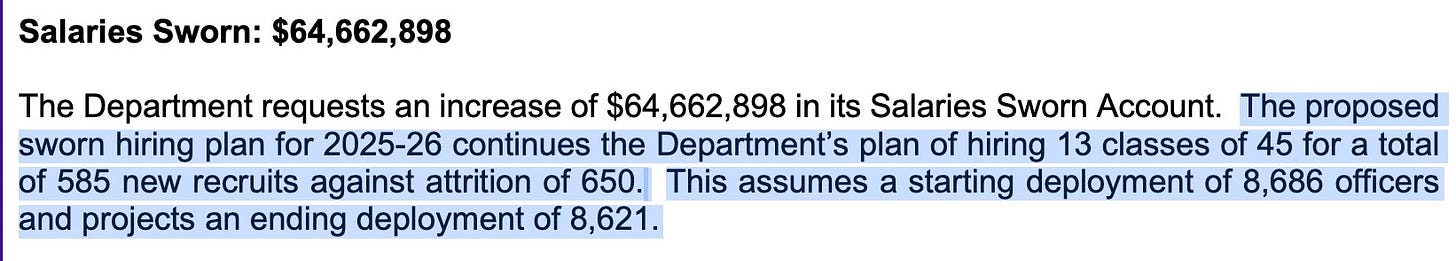

The department has just put forward its budget request for the next fiscal year. The request proposes a $160.5 million funding increase, with $145 million of that going toward obligatory salary and overtime increases as a result of the raises. But despite this 8% funding increase amid a citywide deficit, this budget assumes that officer staffing will continue to fall.

Now THIS I have never seen before. An LAPD budget request that projects a staffing decrease?? That is… new. These requests always lean on very rosy projections to get to a number of recruits that exceeds attrition. And these projections are, yes, quite rosy — class sizes are reduced to 45, but that’s still a number the academy hasn’t hit for years.

So even in the most optimistic staffing projection, one that LAPD has shown no recent ability to achieve, we’re going to be spending even more money on even fewer officers next year. Like someone with the flu who keeps wiping his nose with paper towels because he is out of tissues even though it is now actually shaving skin off his nostrils, we seem to be unable to stop ourselves.

There are probably more conversations to be had about what troubling incentives might be created by a correlation between the presumption of increasing crime and police union leverage in labor negotiations. Or how officers might be deployed differently — the estimates I’ve heard are that only 300 or so officers of the 8,700+ are on patrol at any given time, but overall deployment is something of a black box even for Police Commissioners and elected officials. Or we could discuss building out a much cheaper and easier-to-hire staff of unarmed responders to handle nonviolent offenses that the police union wants their officers to stop enforcing, or traffic enforcement which the same union has said you will pry from their cold dead hands.

But those conversations are for later. Now is for night sweats and coughing something up into the sink.

I've always wondered what a crime and police analysis written by a Garbage Pail Kid would be like and now I have my answer.

curious to see the attachment to traffic enforcement - traffic fatalities are up in most cities i believe, and the perception at least is that enforcement has been down since the pandemic. i live in philly, not LA but we have some of the same trends and struggles, albeit on a smaller scale (beleaguered progressive DA, terrible mayor doing awful things to unhoused people, homeowners losing their minds over the existence of bike lanes, etc). good newsletter!